England still have problems. Their two fixtures this week against Italy and Germany have provided more questions than answers. Before the opening game against Iran at the World Cup, the team will have just seven days to make some ground up. Here are the important takeaway points from the September international break.

3-4-3:

England may well play a back-three against Iran, or they may well set up in a 4-3-3. What certainly is likely, is that England will use both shapes throughout the competition at various points. This camp was used to polish their 3-4-3 formation, but there were notable issues in practice.

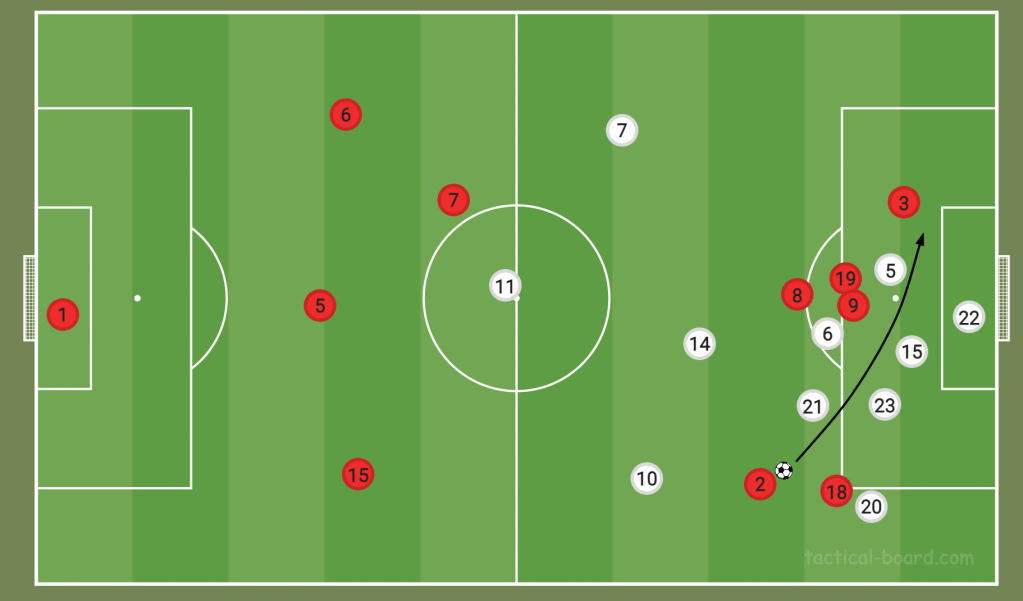

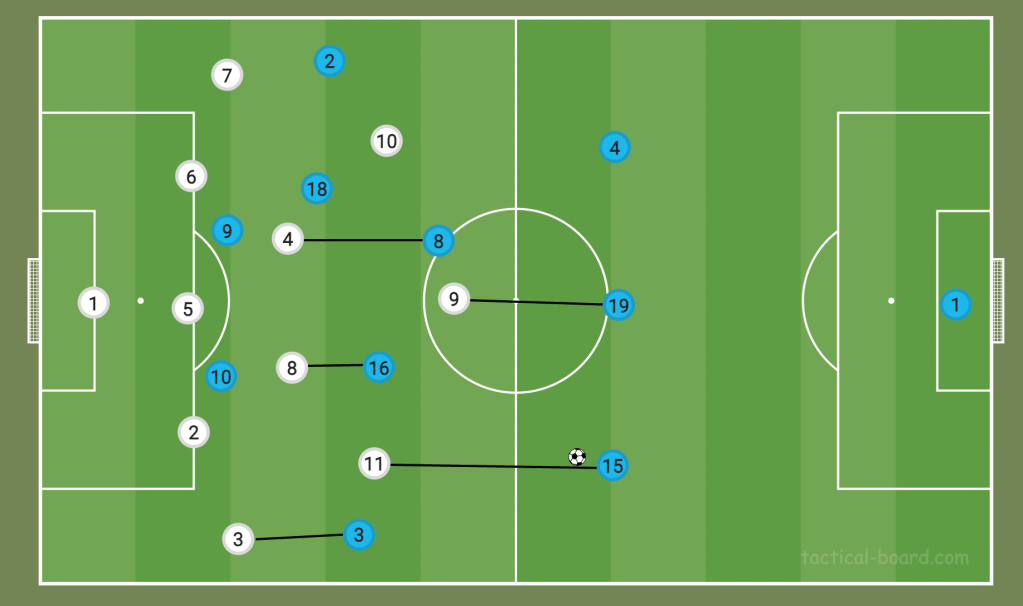

This formation is rarely used by sides who want to chase the ball very high and regain possession quickly. This is because of the fact that a team deploying this shape will usually be outnumbered two-v-three in midfield. There are ways to effectively press using a 3-4-3, which involve marking the two midfielders closest to the play, leaving the opposition’s most advanced midfielder (such as Nicolò Barella for Italy) free between the lines, and using a wide forward to press the player on the ball, as shown below.

However England were not brave in their pressing against Italy, and instead worried too much about Barella, meaning a closer option was always on for Italy’s centre-backs.

This contributed to the lack of possession England had in both matches. It wasn’t helped by the fact that the team dropped into their low-block shape particularly early, sometimes while still in the midfield phase. This invited pressure from Italy and Germany and meant that England were camped in their own box for long periods.

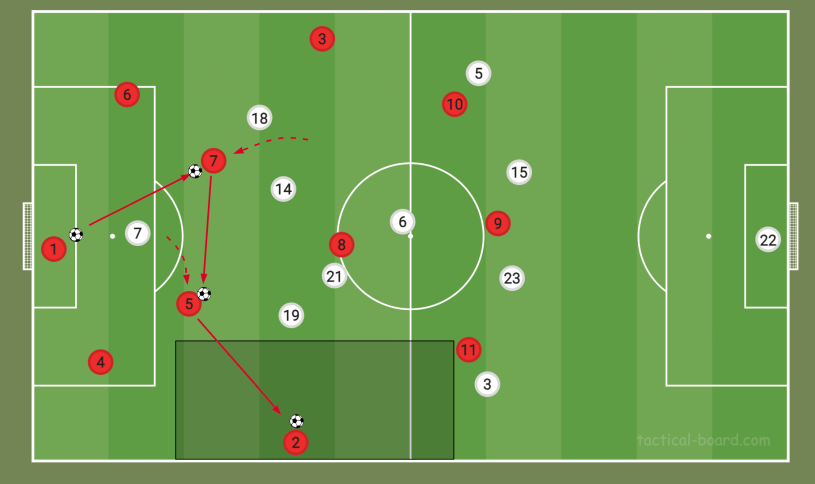

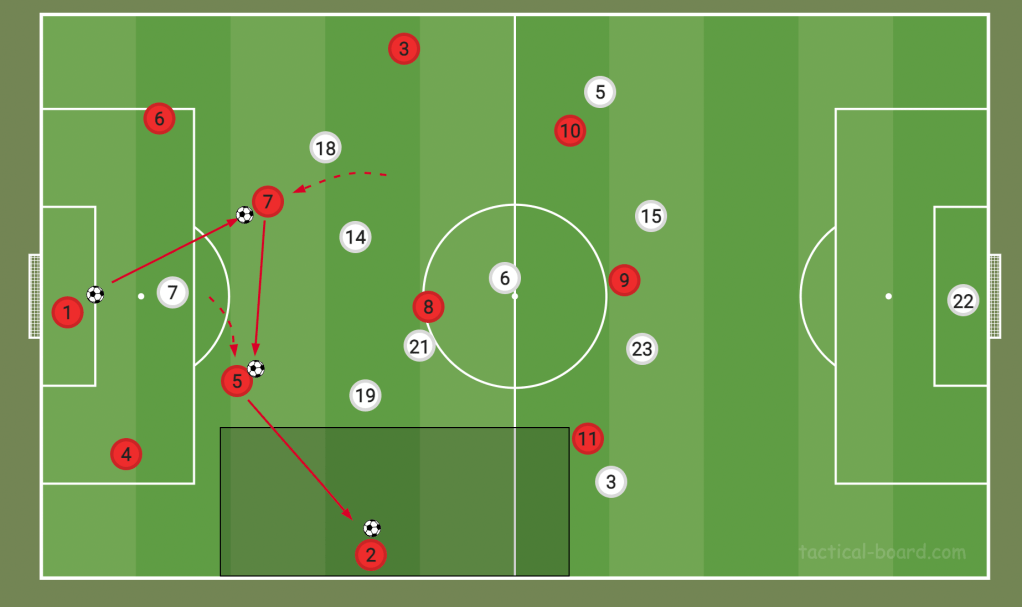

On the ball, England were regularly stifled by Italy and Germany’s pressing, and were forced into undesirable areas far too easily. England’s Plan A will have been to build up through wide zones, bypassing Germany’s obvious numerical advantage in the centre of the field. The best way to do this, is to begin with a pass into a central midfield player or central defender, as it draws the opposition into a tight, compact shape, at which point a wide pass can be made to a wing-back — now suddenly with room to run into ahead of them.

However, Germany knew this, and deliberately blocked off a central pass in the first phase, meaning England were forced wide too soon. Frequently, Nick Pope passed to Harry Maguire, who could only pass to Luke Shaw. By the time Shaw received the ball, Germany had numbers around the ball.

Declan Rice could have dropped in with Eric Dier shifting to the side, but this wasn’t attempted at any point.

England will have to be better at nullifying an opponent’s high press during the World Cup.

Rice and Bellingham:

In midfield, England started Rice alongside Jude Bellingham for both games. The pair have played together before, and formed an exciting partnership, but only really in a three-man midfield.

Being the only two in the centre this week, they adapted well to the high transitional demands from defence to attack and vice versa, since they are both better described as ‘runners’ in midfield, as opposed to ‘ball-players’ such as James ward-Prowse, Joshua Kimmich or others of a similar mould. This helped England when possession changed hands. However, on the ball, England struggled to produce quality in long deliveries or short passes, and on occasion, balls into the front-three were not of the calibre required.

Wing-backs:

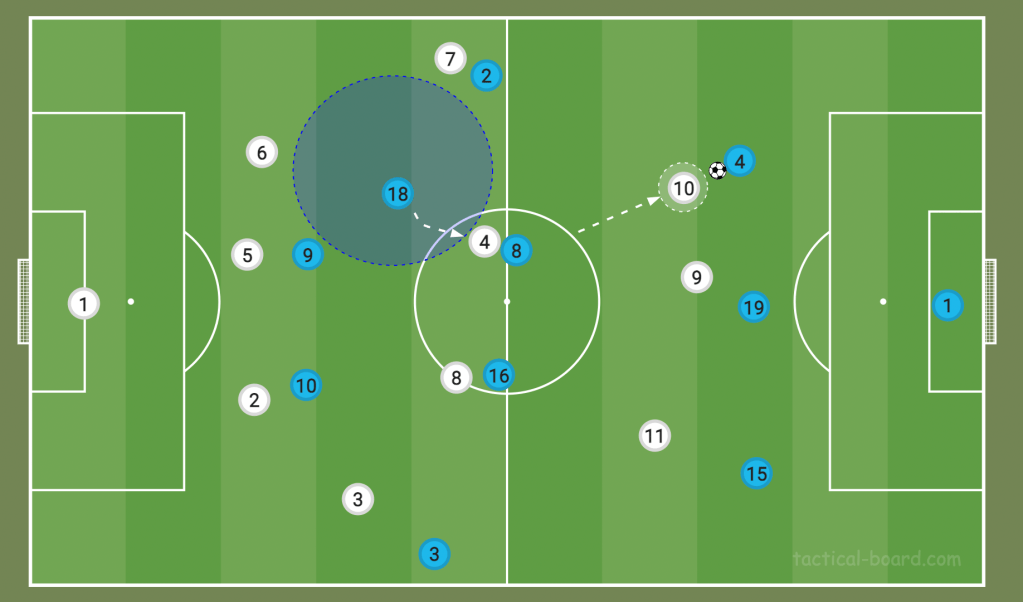

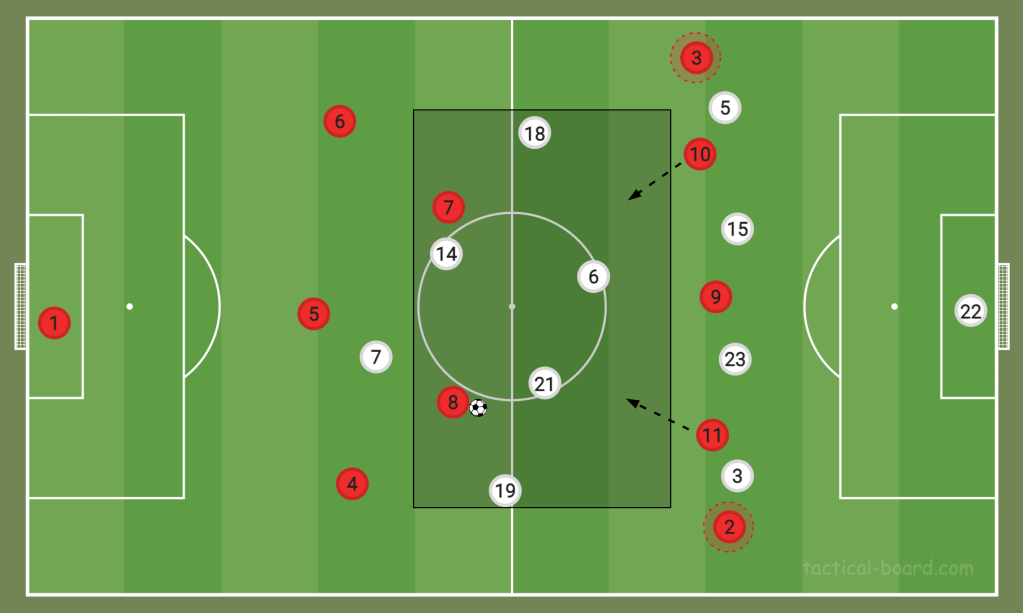

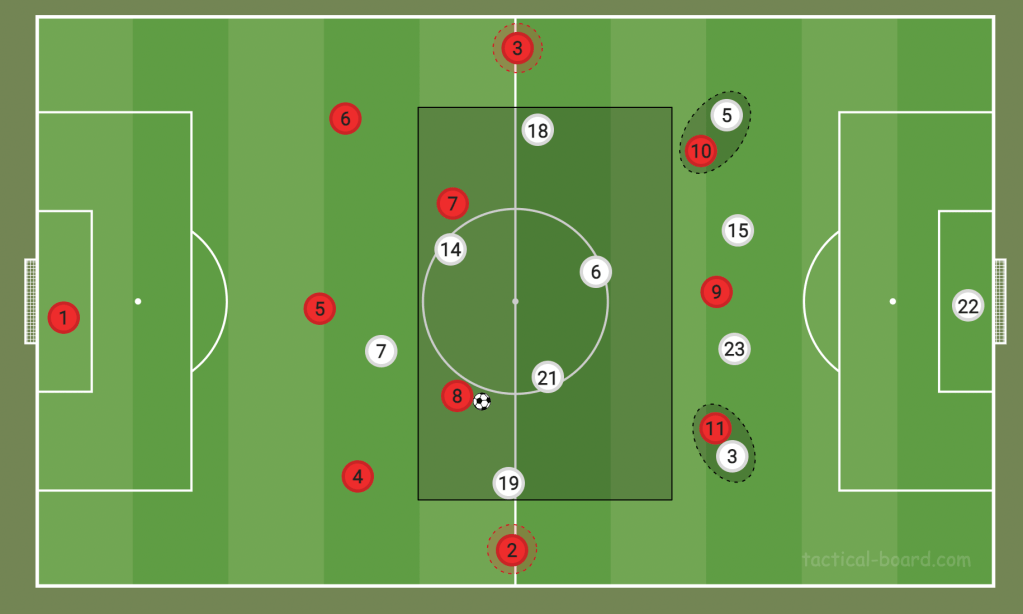

The easiest way to gain control in midfield when using a 3-4-3 is to deploy a four-man box, in which the two wide forwards drop in to link up with the two central midfielders. Raheem Sterling and Phil Foden are comfortable doing this, but it can only be carried out if the wing-backs have advanced high enough to pin back the opposition full-backs.

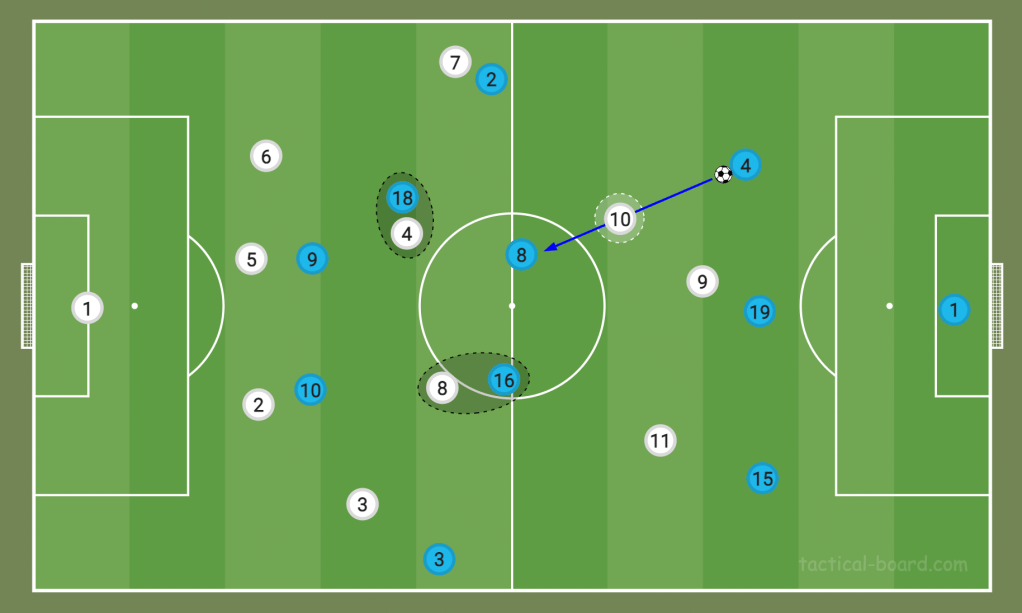

Reece James and Luke Shaw, although much better against Germany than Italy, took too long pushing up the field in build-up, meaning Sterling and Foden were unable to move off Germany’s full-backs and into midfield. For this reason, England struggled to control the game for more than a few minutes at a time.

A lot has been made of England’s left-back/left-wing-back position this year, with Shaw and Ben Chilwell sitting on the bench for their respective clubs. Gareth Southgate trialled Bukayo Saka there for the Italy game, which didn’t pay off at all. Saka hasn’t started at wing-back since his fourth England cap back in 2020, and that was obvious.

Shaw was one of England’s best players against Germany, able to track back and push up at the right times, and to great effect. His goal was almost a carbon copy of the one he scored in the Euro final against Italy last year, with the right-wing-back crossing the ball in and Shaw arriving as the fifth attacker — creating an overload in the opposition box. This type of goal is the very reason England play a back-five against some major nations and Shaw may have secured a starting place against Iran if England are to stick with a 3-4-3.