The World Cup in ‘06 was won not by the greatest players, but by the greatest system. This World Cup winning team is one of the finest examples in football history, of a system being far more important to success than personnel.

Manager Marcello Lippi was blessed with midfielders, especially in Andrea Pirlo and Francesco Totti, who became central to the way Italy played en route to winning the tournament. Not only did Lippi’s innovative tactics baffle the competition in 2006, the system inspired that of Spain in 2008, who went on to win the Euros that year.

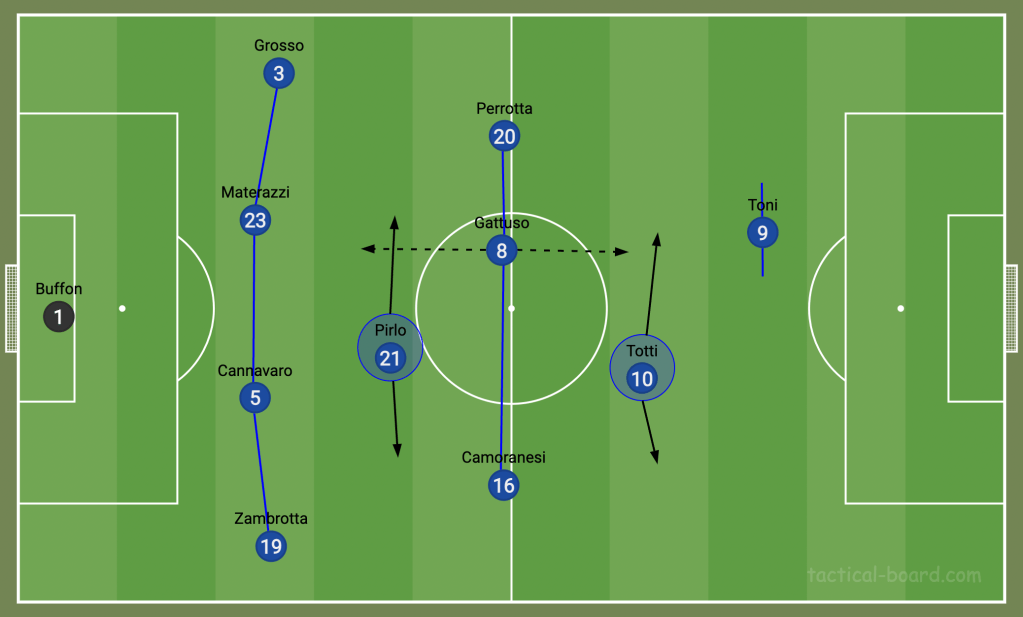

Italy’s play revolved around Pirlo and Totti, who were playmakers behind and in front of the midfield, respectively. Pirlo the deep-lying No 6; Totti the creative No 10. Defending teams had to treat Totti as a striker and a midfielder at different times, causing confusion and errors in communication.

At the time, football had never seen such a staggered iteration of the 4-4-2. It allowed Italy to control games in midfield, where most of the play would take place.

It’s worth noting the role of Gennaro Gattuso in midfield too, who had to do most of the vertical running, linking defence to midfield, and midfield to attack. The nature of Pirlo’s and Totti’s roles on the ball meant that without Gattuso, Italy’s team would have become static and disjointed.

Italy’s final two midfielders — their wide midfielders — were in fact rarely wide at all. This being the key to them controlling games in midfield, Simone Perrotta and Mauro Camoranesi were really central players in disguise. Both had experience in central midfield as well as out wide at club level, so their prior experience played a big part in allowing Lippi to deploy them in this way.

Used functionally, Perrotta and Camoranesi would spend most of their time serving the requirements of Pirlo. Since the AC Milan man was arguably Italy’s most important player on the ball, opposition teams began to target him as a player to man-mark out of the game, preventing him from receiving the ball or moving it on to a teammate.

Therefore, as shown above, Perrotta and Camoranesi would invert to shield Pirlo from an opposition press, along with Gattuso from in front as well. They would usually take up areas in the half-spaces, leaving the full-backs as Italy’s only wide players.

This remained an essential part of Italy’s national team tactics throughout Pirlo’s career, even up to Euro 2012, during which a 33-year-old Pirlo was protected by Claudio Marchisio, Riccardo Montolivo, and Daniele De Rossi.

Off the ball, Perrotta and Camoranesi screened the defence, keeping narrow to fill the gaps in front of Italy’s back-four. This was crucial, given that Pirlo was not naturally a ‘screening midfielder’ — adept at performing those defensive duties alone. With a narrow midfield, it meant other countries had to attack predominantly out wide, which posed less of a threat to Italy, and helped them in keeping five clean sheets in their seven matches at the World Cup.

When playing out from the back, Pirlo would drop between the two centre-backs, creating a back-three. Lippi insisted on this as a way of beating the first line of pressure in the final against France. Gattuso would sit just behind the first line of pressure, as an option for Pirlo to play to — immediately penetrating through into midfield.

Gattuso was well-drilled in which areas to take up, and when. Italy used French captain Zinedine Zidane’s movement as a trigger. If he joined his team’s front-three to make a four-man press (standing halfway between Pirlo and centre-back Marco Materazzi), then Gattuso would be central, and Pirlo would play a pass through the middle between Zidane and Thierry Henry, as shown below.

Whereas, if Zidane decided to get tighter to Pirlo by coming more centrally, then Italy could play out through Materazzi or Pirlo, with Gattuso dropping into the left-half-space to receive a pass in the gap left by Zidane.

This worked so well because other countries were unlikely to commit more than four players to the initial press, and so Italy would always have an overload in the first phase.

The system in practice looked more like a 4-1-3-1-1, but, put simply, was the most effective way for Italy to use the universal 4-4-2 shape, getting the best out of their players. Spain’s similar use of inverted wingers and a second striker like Totti won them Euro 2008 two years later, and Italy remained a dangerous side with a very similar formation for almost a decade longer.