This must be Liverpool’s most impressive victory over Manchester City in recent years. They had to deal with a genuine Man City striker for the first time since Sergio Agüero, while also trying to break down a robust defence without the likes of Sadio Mané.

Klopp’s side didn’t see much of the ball throughout the game, and spent long periods trying to disrupt Pep Guardiola’s possession-based football.

Liverpool set up in a 4-4-2 shape off the ball, with midfielder Harvey Elliott moving to the right side of midfield. Man City built up with a back-three, and two central midfielders in the first phase. Liverpool’s forwards Roberto Firmino and Mohamed Salah focussed on blocking the passing lanes from the centre-backs into the two midfielders, and Elliot and Diogo Jota kept very narrow — blocking the passing lanes into Man City’s more advanced midfielders Bernado Silva and Kevin de Bruyne. This was enough to prevent Man City’s central players from being involved in build-up, leaving just the two spare defenders as passing options.

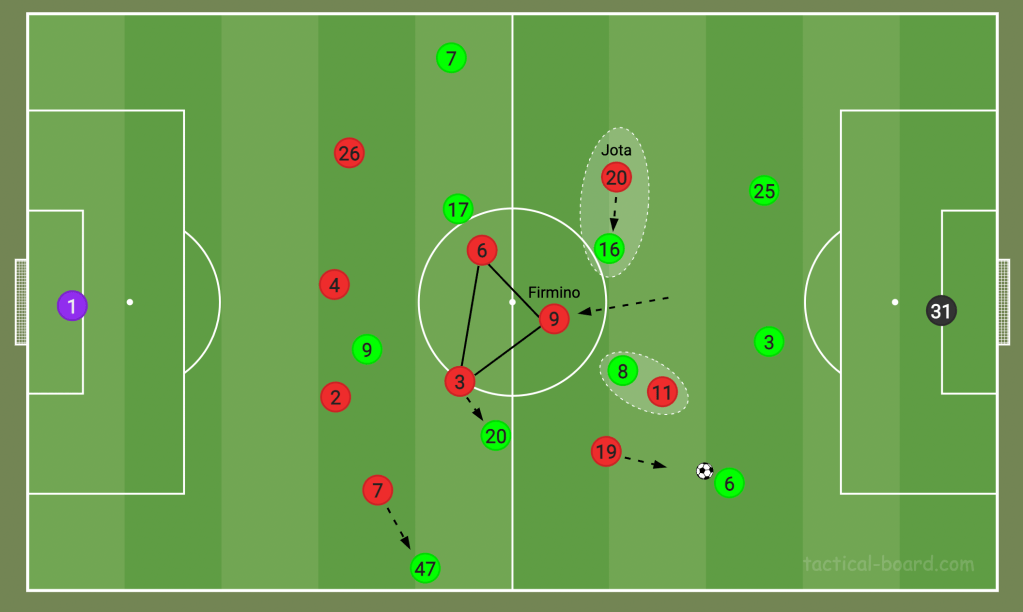

When the ball was played to right-centre-back Manuel Akanji, Liverpool would transition into more of a 4-3-3, their favoured shape. The key player in this transition was Elliot, who would drop in from right-wing to centre-midfield, leaving Firmino and Salah to block central passes (just as before), and Jota to press Akanji.

To help progress forward, De Bruyne would often drift into Man City’s right-half-space to receive a pass out wide from Akanji. At this point, Liverpool’s No 6 Thiago would follow De Bruyne’s movement, and Fabinho and Elliott would have to become the midfield pair.

Man City preferred to play to the left side, however, where Nathan Aké was. This is because Liverpool’s transition here was slightly different, and difficult to carry out seamlessly.

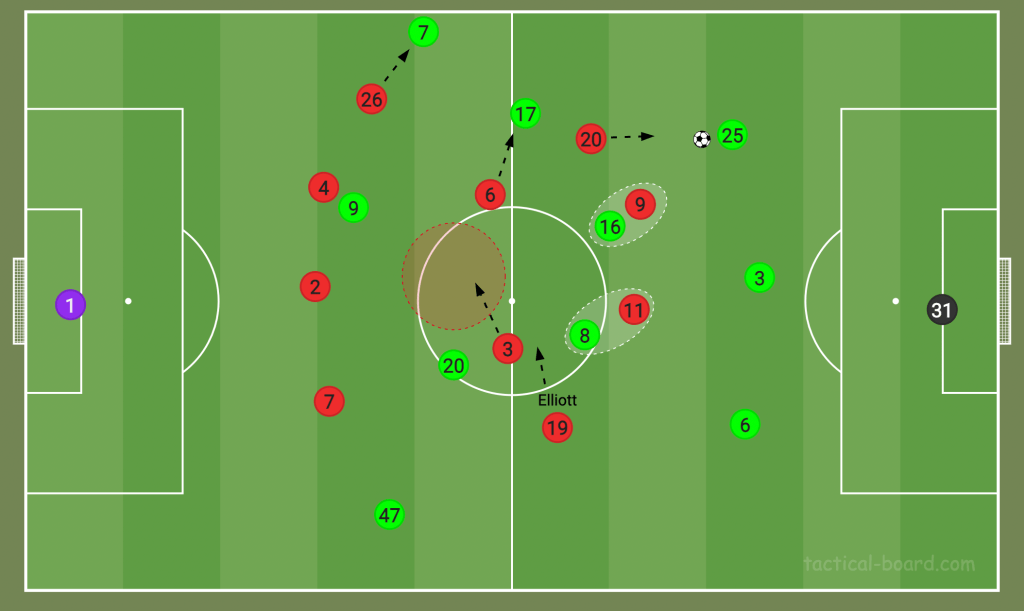

Elliott would press Aké, and Salah kept blocking the central pass to midfield. However, Firmino was not able to join Salah in doing this like before, since that would leave Jota dropping into a midfield-three, which would be unfamiliar territory for the Portuguese forward. Therefore, Jota would shuffle over to track the run of Rodri, while Firmino would drop into a No 10 midfield role, just ahead of Fabinho and Thiago. This effectively created a 4-2-3-1, as seen below.

The purpose of both of these transitions was to apply pressure to Man City’s wide centre-backs, and block passes into the middle of the pitch — where Guardiola’s team prefers to play.

When Liverpool received the ball, they would often be in a situation whereby they could counter-attack at pace. This is how they got their all-important goal. However, when they were building up in a more controlled way, they too deployed a back-three, with left-back Andy Robertson darting upfield level with Man City’s last line.

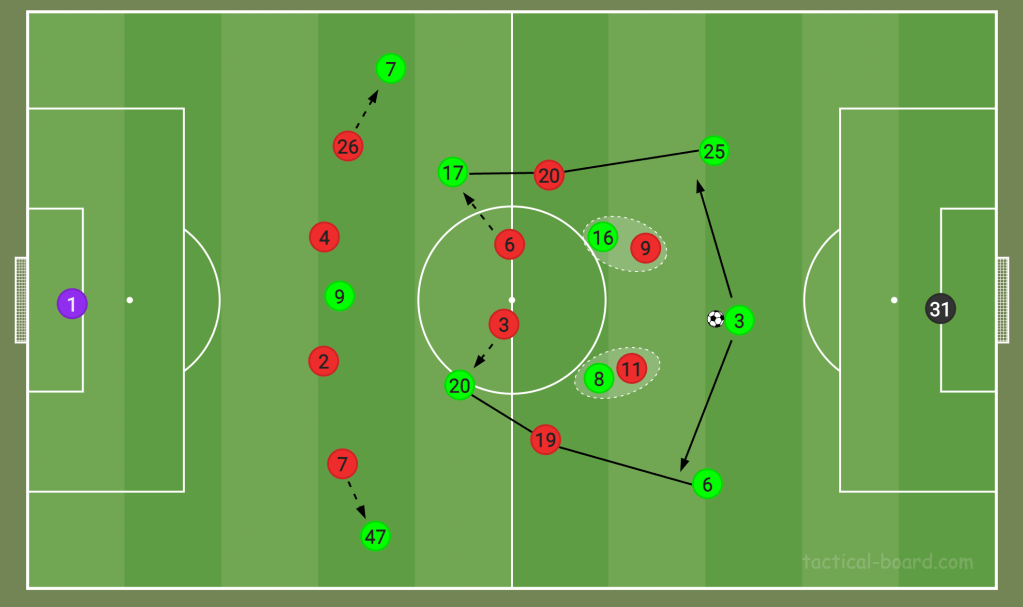

On the left side, Jota and Firmino would take it in turns making a third-man run into midfield to help create numerical superiority, and, on occasion, would both drop in together — creating a box through which they could dominate the midfield.

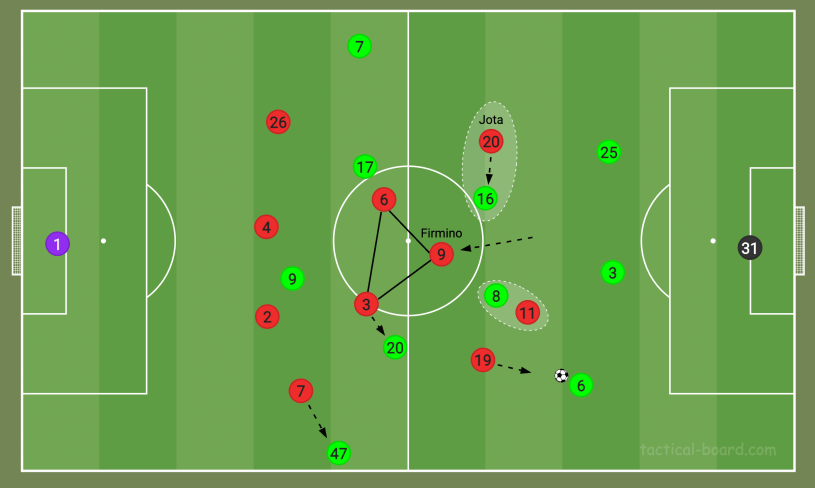

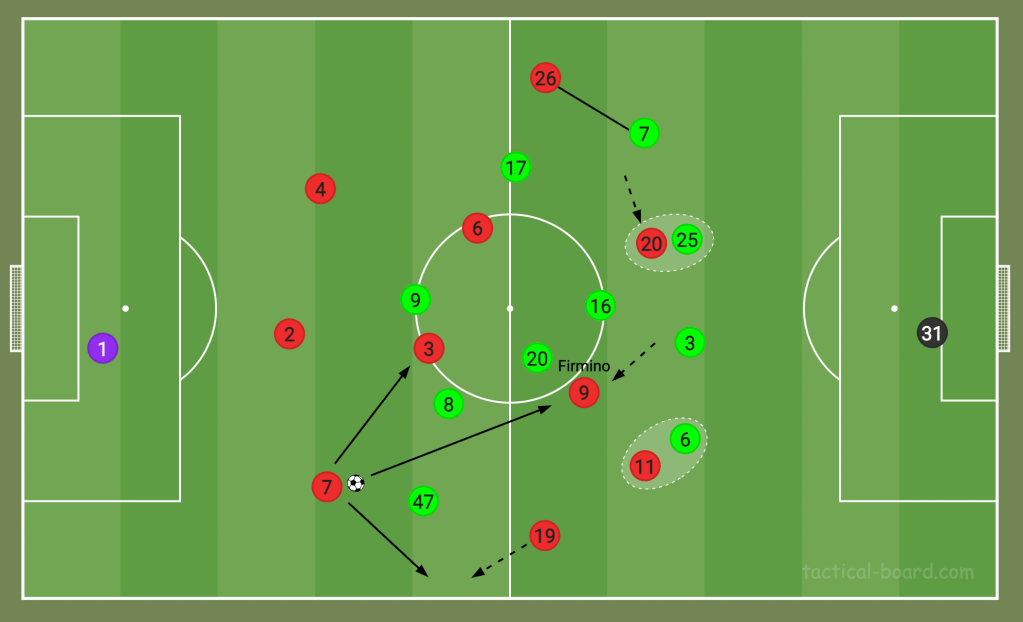

On the right, in false-9 fashion, Firmino would peel off the back-line and into midfield again, on the blindside of Bernado Silva. He was able to make this run unmarked a lot. Jota would then drift more centrally to fill the space Firmino vacated, and Robertson would push up as a winger on the far side. Firmino was key in build-up, and was often the player receiving the first pass from defence into midfield.

Liverpool’s constant rotations caused issues for Man City’s back line. The positioning of Klopp’s players when in possession was unpredictable and it forced the likes of Aké and Akanji to make split second decisions over whether or not to track a runner or to keep their shape.