With the World Cup just five days away, the favourites are known, as are the ‘dark horses’, but if history tells us anything — it’s that all bets are off once the competition starts. This has always been the case. Well, apart from one particular four-year period; a blip in the system. The Spain team of 2008 surpassed all expectations to lift the European Championship trophy in style. What followed was the most dominant four-years in football history. What did the best national team ever look like, and how did they stay on top?

2008:

Managed by Luis Aragonés, Spain set out to be hard to beat. Perennial underachievers of the game, they developed a style of football known in all its glory as Tiki-Taka, but which was more of a pragmatic attempt to limit the concession of chances to their opponents. Possession-based football would be Spain’s best way to defend.

Later in their four-year reign at the top of world football, Spain became adept at counter-pressing, but at Euro 2008 they were their most passive off the ball.

Aragonés played a 4-1-4-1 off the ball, which would turn into a revolutionary iteration of the classic 4-4-2 in attack. Spain had the likes of Xavi and Iniesta and David Silva in their team, all of whom were masters in possession, and could dominate a game if afforded the time and space. The key to accommodating this was the inclusion of defensive midfielder Marcos Senna. Knowing he would always be sweeping up in front of the defence, Xavi and Iniesta and co could express themselves that bit more freely.

It made sense for these players to be in close proximity, since Spain’s two full-backs Joan Capdevilla and Sergio Ramos were willing runners who liked to join in with attacks from wide areas. Keeping the bulk of the midfield in the central three zones meant that short passes were easy to find, which fit their possession principles nicely.

Spain had just one wide attacker in their squad. David Villa of Valencia CF was a smart footballer, and drifted all over the pitch while his teammates further back kept the ball. His role was to disrupt the defensive organisation of the opposition with a view to creating space either for himself or for a teammate. His role in Spain’s team had changed by 2010, but at Euro 2008 he was something of a decoy forward (who dropped back as a wide midfielder in defence). The inspiration for this came from the Italy team of 2006, in which Francesco Totti linked the play from midfield to attack by occupying the space in between the lines.

A typical attack would involve the centre-backs finding Xavi with a short pass to break the first line of pressure. With Xavi facing forward, this was a trigger for Iniesta and Silva to make inverted runs towards the centre of the field. Xavi would find one of them, and the team would be set up for their possession football already.

What became clear over the course of the tournament is that the movement from Iniesta and Silva would force the opposition to bunch together in a narrow structure, leaving far too much running room on the flanks for Spain’s full-backs to maraud forward. Teams couldn’t defend both the midfield passes and the runs from the full-backs, so they had to make a choice.

2010:

After Aragonés left, Vicente del Bosque took charge of the side. The decline of Marchena and retirement of Senna left gaps in pivotal positions on the pitch. They were replaced by Barcelona duo Gerrard Piqué and Sergio Busquets respectively.

Much like everyone at the time, Del Bosque tried to implement more width higher up the pitch, by bringing in more traditional wingers. In fact, the 2010 World Cup is famously known as the birth of 4-2-3-1 on the international stage. Spain were only able to do this because Xavi started playing higher up the pitch, protected by two deep midfielders now, not just Senna. Xabi Alonso and Busquets complemented each other’s style well, and when Alonso joined in with attacks, Busquets would emulate Senna’s role in the 2008 team.

Spain lost their opening game of the tournament 1-0 to Switzerland, and were exposed on their left channel. Villa, playing on the wing, liked to stay high, and Capdevilla at left-back (not one of the bigger names in the team) found himself overloaded — which is something Switzerland exploited a lot.

For the rest of that World Cup, Torres started from the bench, and Pedro came in on the wing, meaning Villa played as Spain’s out-and-out striker.

As teams began to defend deeper against Spain, fully aware they could not challenge them for control of the ball, Spain had to work harder to move the ball and create opportunities. Their average number of passes per shot rose to 44, up from 33 two years earlier. Chances were scarce. Some called it boring.

Del Bosque, like Aragonés, still didn’t feel comfortable pressing high up the pitch. He felt this would detract from the compact shape his team deployed when defending. Typically in the mid and high blocks, we would see Villa apply a little bit of pressure — enough to prevent a run into midfield — supported by those behind him like Xavi, Iniesta and Xabi Alonso, who would block opposition passing lanes into midfield.

Once again, this tournament was won not by creating lots of chances, but by preventing the opposition from doing so. Spain’s possession-based game was as good a defensive strategy as it was an offensive one.

2012:

Spain had benefited from playing without an orthodox striker in 2010, and replacing it with a winger. Del Bosque went one further in 2012. He didn’t field a forward of any kind.

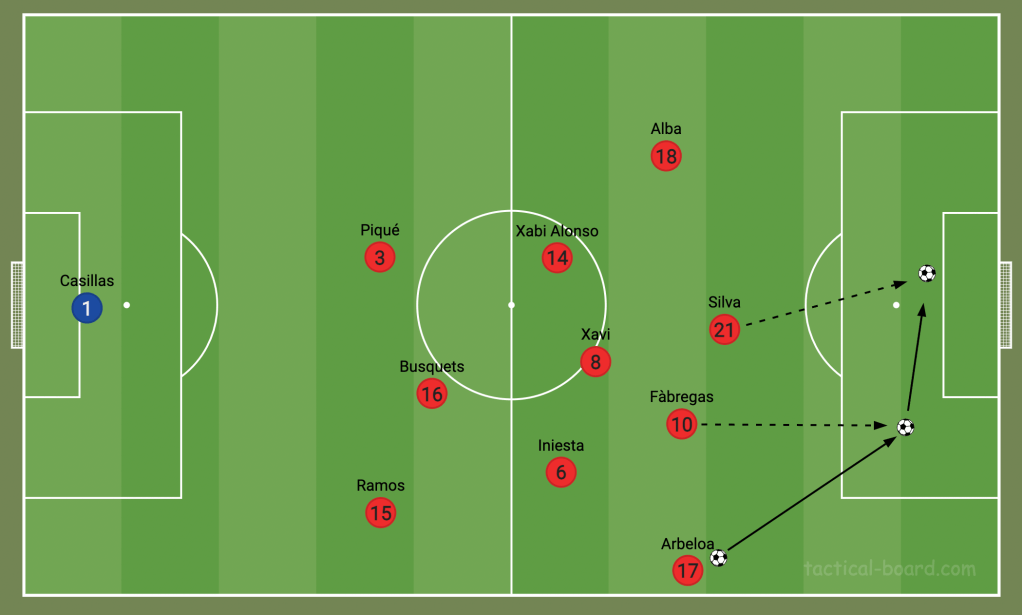

Helped out by the tactical use of Francesc Fàbregas in Barcelona’s 2011/12 team, Del Bosque was able to bring the 25-year-old into his lineup to replace the ageing David Villa. Spain played a 4-6-0 formation, packing the midfield with not only numbers, but quality. Xavi, Busquets, Xabi Alonso, Iniesta, David Silva and Fàbregas all started. It was the bravest tactic used in the international game for years. And it was utterly foolproof.

After drawing their opening game with Italy 1-1, Spain went on to win all their remaining games, scoring 12 goals and conceding a grand total of zero. In fact, Across these three tournaments, Spain didn’t concede a knockout goal at any point. That may never be done again.

New faces came in at full-back. Jordi Alba and Álvaro Arbeloa were just as energetic as their predecessors. Ramos moved to centre-back to make up for Carles Puyol’s retirement.

They controlled the ball more than ever, with a total of 63 percent of possession across the whole competition, and 58 passes per shot — up 14 from 2010.

Xavi stayed higher, meaning even with a team of central midfielders, Spain could still exploit wide areas by shifting across and creating overloads. Having vacated the forward area completely, they relied heavily on third man runs in behind defences to get in on goal. Fàbregas was particularly proficient here, and David Silva too.

Overall:

It was Aragonés who brought in Tiki-Taka, and Del Bosque took it to the next level in 2010. By 2012, Tiki-Taka was barely a defensive strategy at all, it was simply ruthless. Patient and torturous, Spain’s possession football was unrivalled and unplayable for a three major tournaments.