England’s players and manager Gareth Southgate have been saying all week that they didn’t expect they would be able to create many chances against Iran, emphasising that patience would be key.

One thing is for sure, it didn’t play out that way. England not only dominated the ball — which they would have expected to do — but managed to find gaps where there didn’t seem to be any. That’s the difference between teams who can break down a low block opposition, and teams who struggle to do so.

There were three key ways England were able to manoeuvre their opponents and create high quality chances.

1. Wide rotations

Given Iran’s rather negative 5-4-1 shape (one which they used predominantly to give themselves the best chance of stopping goals, as opposed to scoring them at the other end), England were forced out wide a lot, and were always going to need different ways of finding holes and pockets. The key players at these moments were full-backs Luke Shaw and Kieran Trippier and wingers Raheem Sterling and Bukayo Saka, as well as midfield duo Mason Mount and Jude Bellingham.

On each side of the pitch, England had three players whose movement relied on that of the other two. As seen below for example, the movement of a full-back inside would mean the winger would create the width by pulling wide, and the midfielder would then push up to the last line of defence.

This helped to move Iran’s players out of position. Lots of England’s energy was spent trying to disrupt the defensive structure of Carlos Queiroz’s team.

England knew they would have to do this as opposed to set up in a binary way, with strict instructions for the full-backs to stay wide or for the midfielders to sit and protect against a potential counter-attack, as examples.

2. Decoy runs

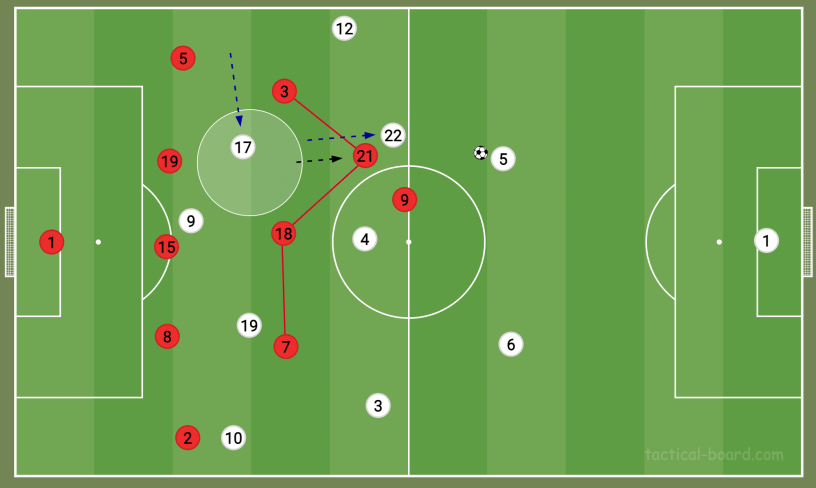

With similar intentions to those of the rotations, there were numerous cases of England’s midfielders or forwards making runs either towards the teammate on the ball or away into space — the aim being to drag an opposition player out of an area that England wanted to exploit.

This is something Mason Mount is excellent at, and Jude Bellingham did this particularly well against Iran. He dropped in towards the player on the ball (often John Stones at centre-back), pretending to offer himself to receive a short pass. By an Iranian midfielder following his run, it left pockets between the lines which Saka or Harry Kane could take up, as seen below.

Decoy runs in behind worked well too. Sometimes when England’s wingers had the ball, Bellingham would make a run in behind Iran’s defence, and drag a player with him in the process. This left holes not to be exploited by other players, but for those on the ball to drive into. This was the chief tactic in place to allow individuals the chance to make forward dribbles with the ball.

3. Attacking overloads

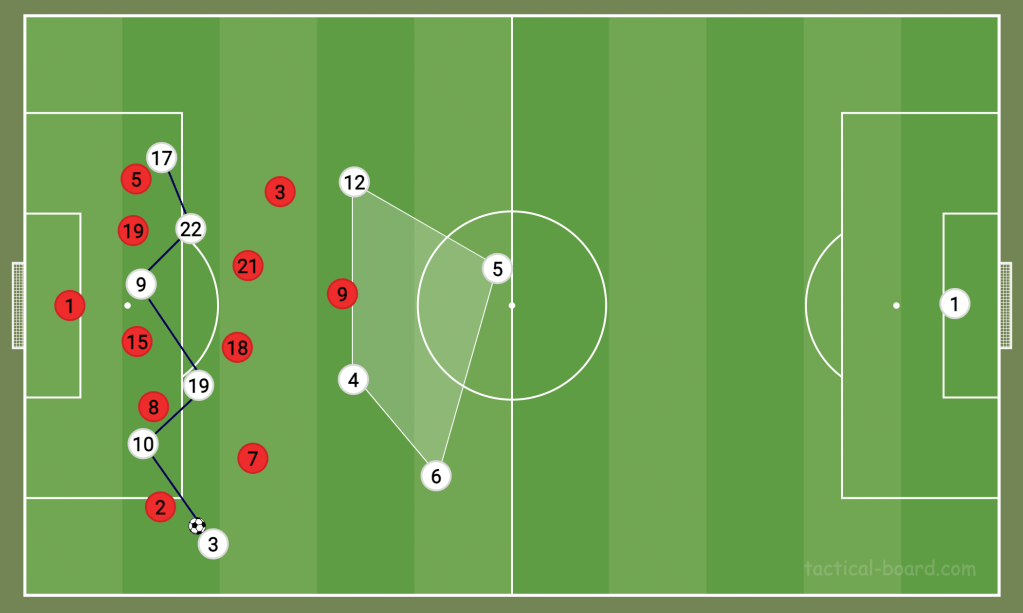

Playing a back-five makes it hard for the opposition to create overloads, without becoming susceptible to counter-attacks. Committing six players to the final stage of an attack leaves just four to protect, which history suggests is not ideal. However, it can be done selectively and at the right times.

This is where having versatile full-backs becomes extremely useful. England would use the front-three, two attacking midfielders, and full-back on the ball side in the final stage of attacks. The full-back would therefore be the widest player — effectively playing as a wing-back temporarily. The other full-back, not involved in the attack over on the far side, would need to play much more inverted, picking up a midfield position behind the attack, as seen below.

Shaw and Trippier are two of the best players in the England squad — along with Jordan Henderson and Trent Alexander-Arnold — at whipping a ball into the box from a deep and inverted position in the half-space. Both Shaw and Trippier have also played important games at wing-back for England, and this meant the team had the quality to play with one inverted full-back and one wing-back depending on which side they were attacking on.