Both Croatia and Morocco have got to this stage on merit. Belgium, Spain, Portugal and Brazil have all been knocked out thanks to these two sides. Morocco have the best defence in the tournament with just one goal conceded; Croatia are on just three. For context, France have let four in, and Argentina five. Those thinking now is the end of the line for either of them might be encouraged to think again. Here’s what we’ve seen from them so far at this World Cup.

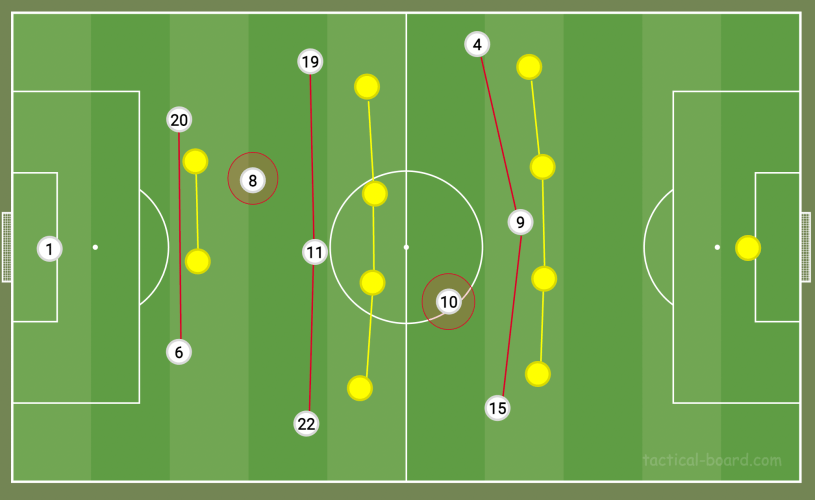

Denying wide overloads:

Both sides have been excellent in a low block, with the 4-1-4-1 shape. We’ve seen that most of this World Cup’s dangerous attackers have been wingers. Croatia and Morocco have managed to deny wingers from being isolated one-v-one against a full-back. Croatia in particular have very defensive wingers, and Morocco are well coached in this area too. They have filled wide spaces with three or four players, which has meant even the very best wingers have been unable to take on defenders.

Closing off a lot of the pitch has helped to keep a narrow structure and has meant other teams’ only route past the low block has been with quick switches of play — which is far from ideal.

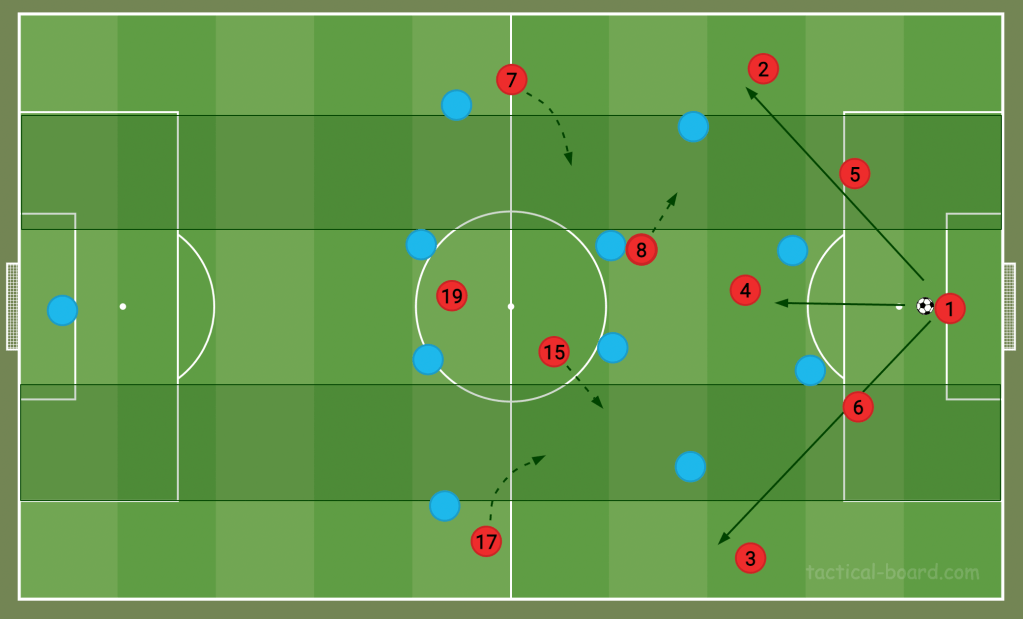

Morocco’s use of the half-spaces:

One of the easiest ways to decide how a team should play is to think about who the best players are, and how to create situations where they can use their skills to good effect. Morocco’s two full-backs and defensive midfielder Sofyan Amrabat have great quality, and so Morocco have used their other players as decoy runners to manoeuvre the opposition’s players out of the way.

As seen below, in build-up, the half-spaces are almost completely vacant (barring the centre-backs). Opponents are attracted to the players and away from the half-spaces too. Since they want to play through Amrabat or the full-backs, Morocco’s wingers and wide midfielders often make late runs into the half-spaces, taking opposition players with them. This frees up the central zone and flanks so that Amrabat can get on the ball with many passing angles, and the full-backs can bomb on forward.

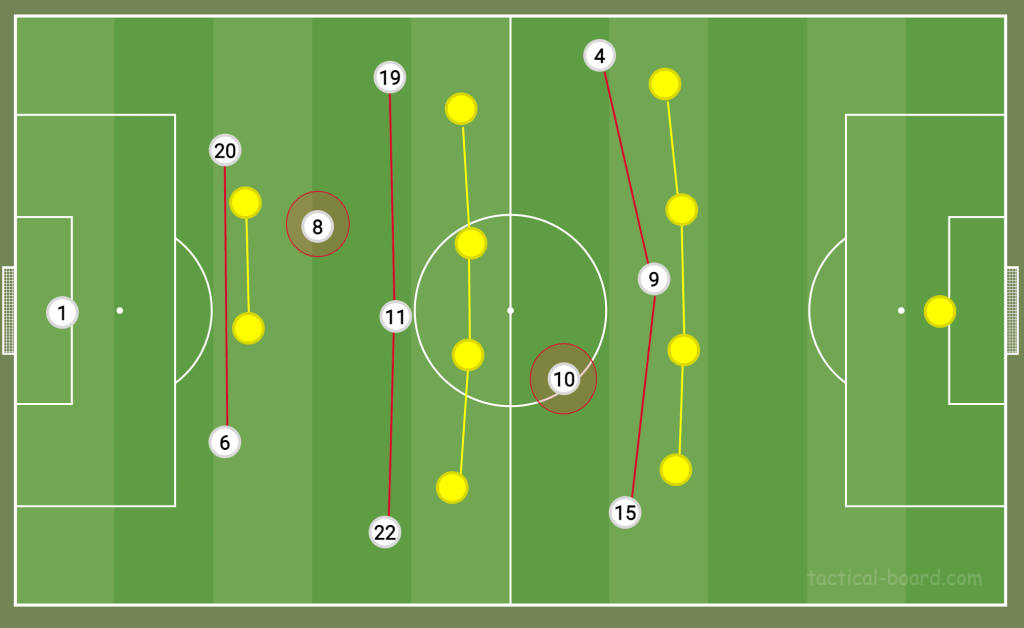

Croatia’s double-playmaker:

Croatia, in build-up, have done something quite reminiscent of Italy’s 2006 World Cup-winning team. Their midfield includes their two best players Mateo Kovačić and Luka Modrić, and so using one as a deep-lying playmaker and the other as a playmaker between the lines higher up means Croatia are able to exploit flat defensive systems and progress the ball up quickly. In 2006, this was Andrea Pirlo and Francesco Totti.

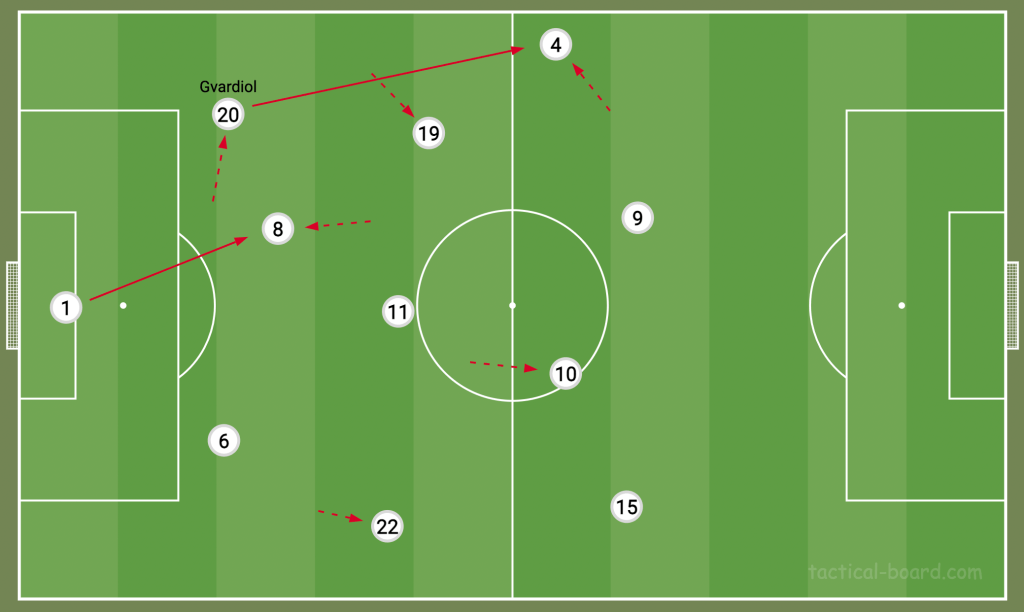

The other interesting advancement in the Croatia team since the side we saw four years ago at the World Cup is that they now have a left-footed centre-back. This may not sound major, but the possibilities for progression on the left side are far greater with a left-footed centre-back. Joško Gvardiol is fast becoming one of the most sought-after defenders in the world. He’s certainly on Chelsea’s radar.

We’ve seen Croatia’s centre-backs split much more than they did in 2018, and this affords Kovačić the space to drop in and receive the ball. What they’ve also done is use their left-back as a decoy to move into midfield instead of up the touchline. The reason this was a smart move is that it means Gvardiol can play straight forward to Ivan Perišić — their creative winger — without needing a bridge pass. Croatia are much more direct as a result.

In short, the inclusion of Gvardiol has opened up two massively helpful passing routes. One from the goalkeeper into Kovačić, and the other from Gvardiol to Perišić.