Tactics move on and the game evolves, but some things never change. Football will always need utility players; unfashionable players used solely to man-mark an opponent or provide cover for an exceptional teammate.

Some of the biggest games in history have been won and lost with the use of man-marking. Bobby Charlton on Franz Beckenbauer in the 1966 World Cup Final, Berti Vogts on Johan Cruyff in the final eight years later, Gennaro Gattuso on Cristiano Ronaldo in the Champions League in 2007, and then about five or six examples of Park Ji-sung keeping some of the world’s most masterful puppeteers at bay.

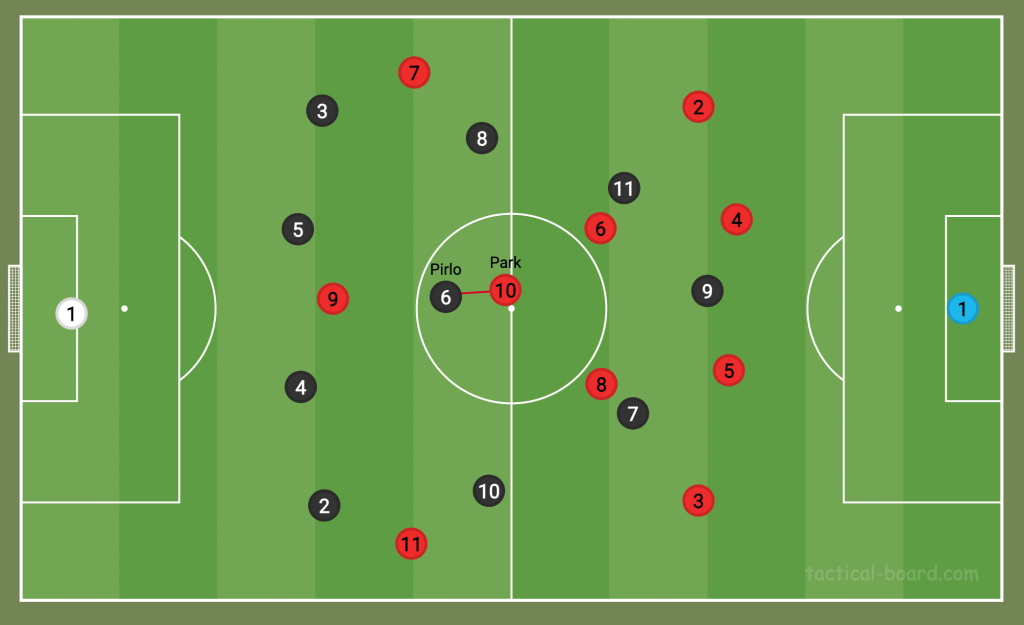

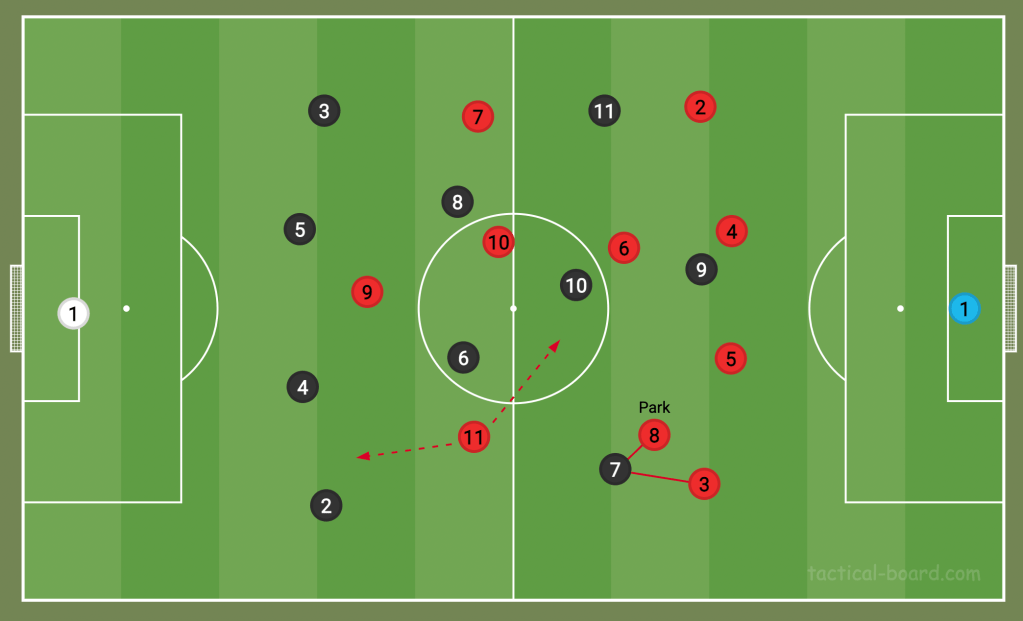

In terms of the creativity he offered going forward, Park was an average midfielder. Manchester United fans didn’t love him for what he did on the ball, it’s the stuff that went unnoticed that earned him his recognition. Park was often played in the big games, with an instruction to nullify the threat caused by an opposition player. He famously kept Andrea Pirlo silent in the Champions League knockout stage in 2010, and did the same to Xavi when United faced Barcelona.

A keen runner off the ball, Park’s work ethic was laudable. For this reason, he never really nailed down a position on the pitch. Some refer to him as a defensive trequartista — effectively taking up the No10 position where he could man-mark the other team’s defensive midfielder. However, the truth is Park shadowed his target wherever they roamed. He was given a function, not a position. He was sometimes used in a double-pivot to mark an attacking midfielder, or he could be employed out wide to track back against a full-back or even double up with Patrice Evra against a winger.

Yes, United often lost a man in midfield or were left vertically unbalanced when Park was playing, but the knowledge that he was causing more damage to the opposition by performing this role was enough to leave his manager Sir Alex Ferguson content. When Park played, both teams effectively played with ten men.

Rodrigo de Paul is a very different type of player. He’s had to be because of circumstance. Both at club level and international level, De Paul plays in close proximity to one of the world’s best players, Antoine Griezmann and Lionel Messi respectively. His role isn’t to man-mark an opponent, it’s to accommodate his fellow teammates, allowing them to play with freedom. What people love about Messi, they can’t unless someone else takes on extra defensive and positional duties. De Paul seems to be that man.

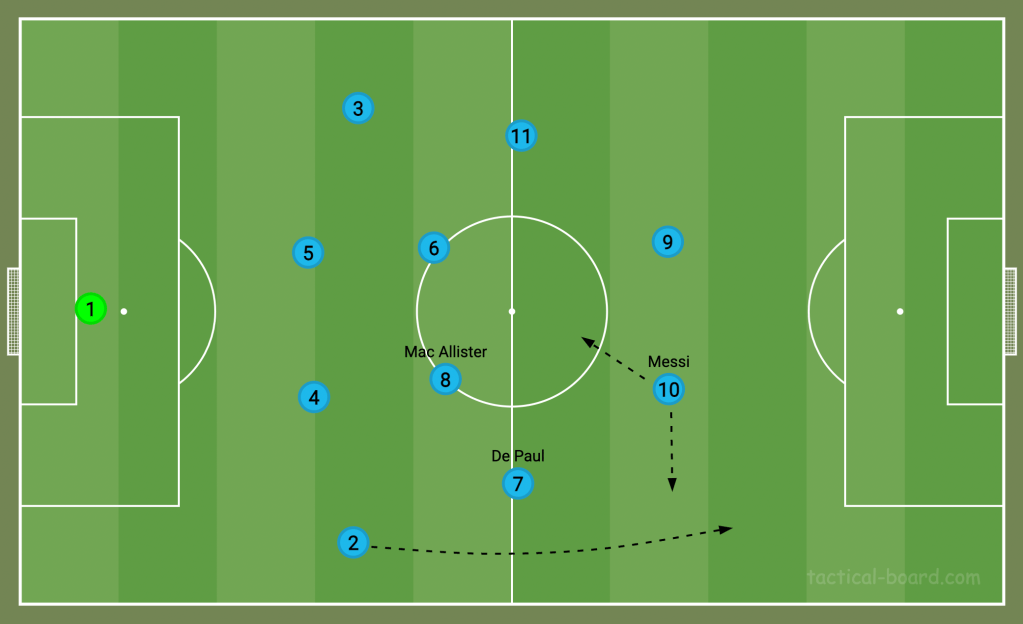

At the World Cup, Argentina played the new 4-4-2 on paper, with Messi up front. But everyone knows Messi will drift wide and come short for the ball at times. For anything Messi could be doing at any one time, Argentina needed to have a plan for maintaining balance. Enter De Paul.

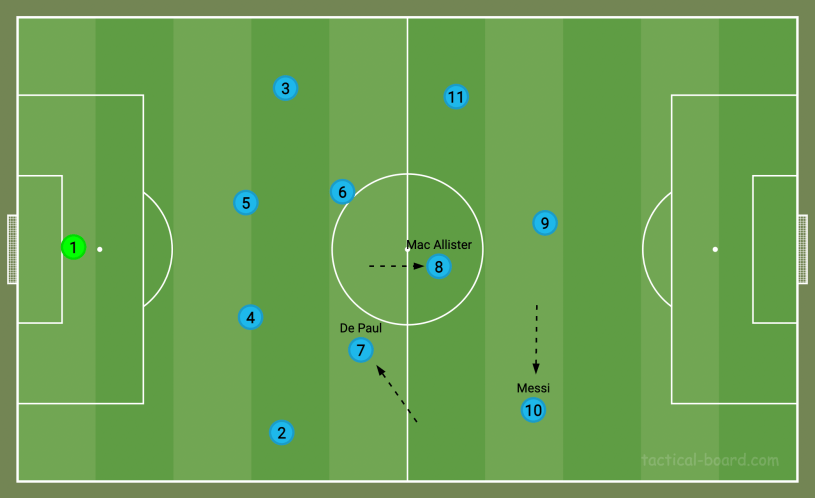

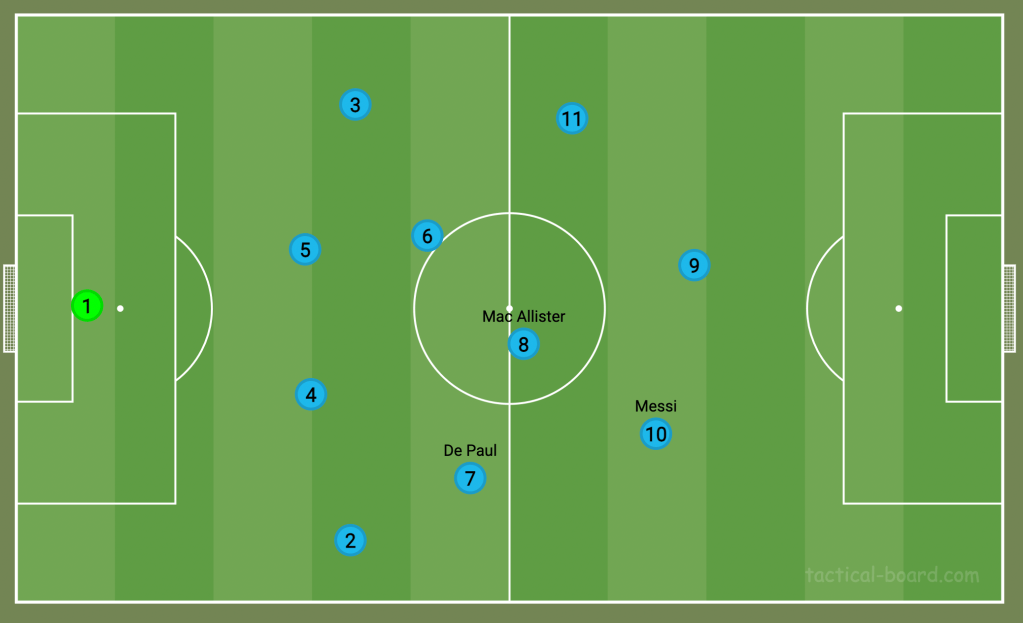

The 28-year-old plays predominantly as a centre-midfielder, but can advance slightly higher up at times. He was used as the right-midfielder in Argentina’s 4-4-2 at the expense of actual wingers because Argentina has to be fluid. They wouldn’t stay in the 4-4-2 all the time. When Messi dropped into the No10 position, De Paul would be the wide outlet (with Nahuel Molina overlapping), and the double-pivot would back Messi up. Messi could drift wide, and so De Paul would take up a narrower position, making the formation look like a 4-2-3-1 instead. Balance would be provided by Alexis Mac Allister who would push up to stagger the midfield.

The average positions taken up by the players looked like the image below, which shows them almost halfway between a 4-4-2 and 4-2-3-1.

Players like De Paul, who are versatile enough to just fill in for teammates when they roam elsewhere, are crucial when you have a talent like Messi in your team. The likes of Park and De Paul will never die out, as football is forever in need of cover and balance. Without utility players, football’s too predictable.