Everyone’s talking about Roberto De Zerbi’s coaching and how Brighton are dominating possession at the moment. His philosophy of build-up is evident, yet no one has mentioned the clear advantage this gives them in progression — solving the pivot problem.

The problem is this: pivot players always have to receive a pass while facing their own goal, but the pivot will usually be man-marked in build-up, making this a problem. That’s why we often see pivots playing the ball straight back to the centre-back again, since they can’t turn or do anything with it.

Under De Zerbi, Brighton create frequent scenarios in which their pivot can receive the ball facing forward, speeding up play and increasing ball retention.

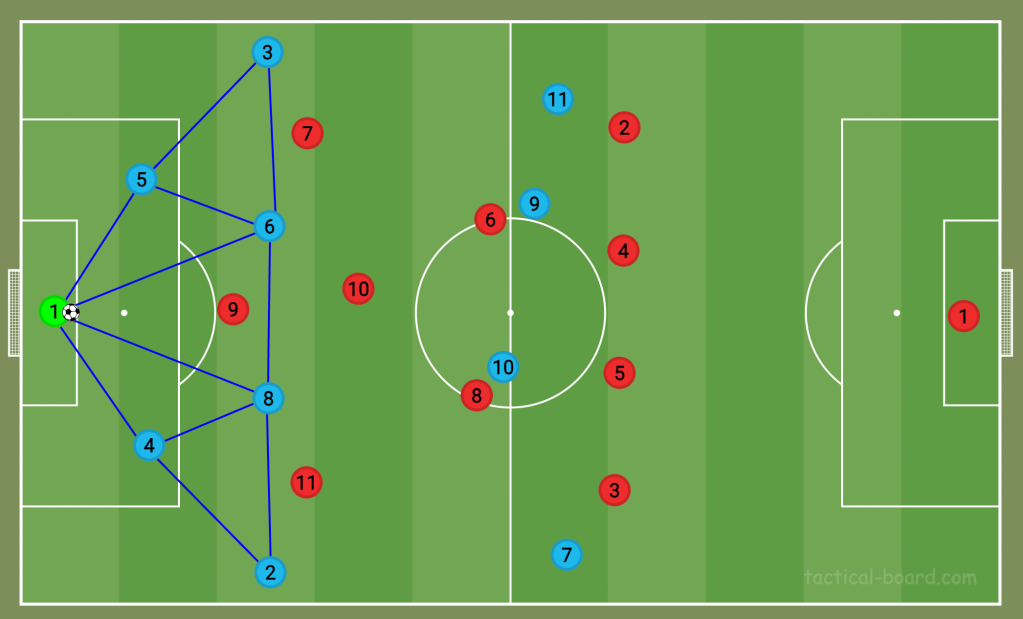

De Zerbi, much like Napoli’s manager Luciano Spalletti, has adopted the 1-4-2 build-up shape. Both centre-backs flank the goalkeeper, the full-backs stay low and wide, and the two pivot players sit ahead of the centre-backs.

This shape in build-up is considered the hardest to defend against in world football as it involves seven players, the most a team will ever need to commit to the first phase. (As a side note, the reason most teams don’t do this is that they feel they could use one or two of these players to better effect higher up the pitch, and believe they can still break the first line of pressure without them). Given the opposition’s goalkeeper can’t help defend, they’d have to commit seven of their ten outfield players to the initial press, which no team will ever do as it would leave their remaining three defenders outnumbered against four attackers.

Brighton’s double-pivot of Moisés Caicedo and Alexis Mac Allister is incredibly deep, with the pair often near the edge of their penalty area. This box they have with the centre-backs creates such a strong foundation for possession that it draws other teams so far out of position, generating more space further upfield.

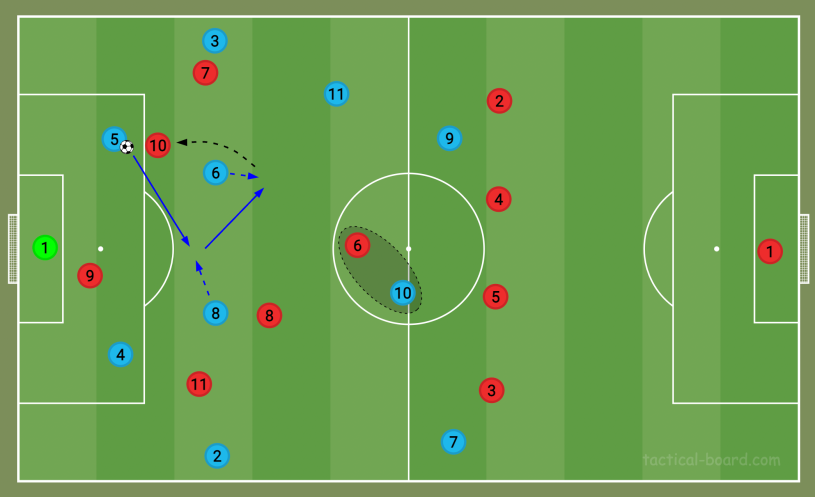

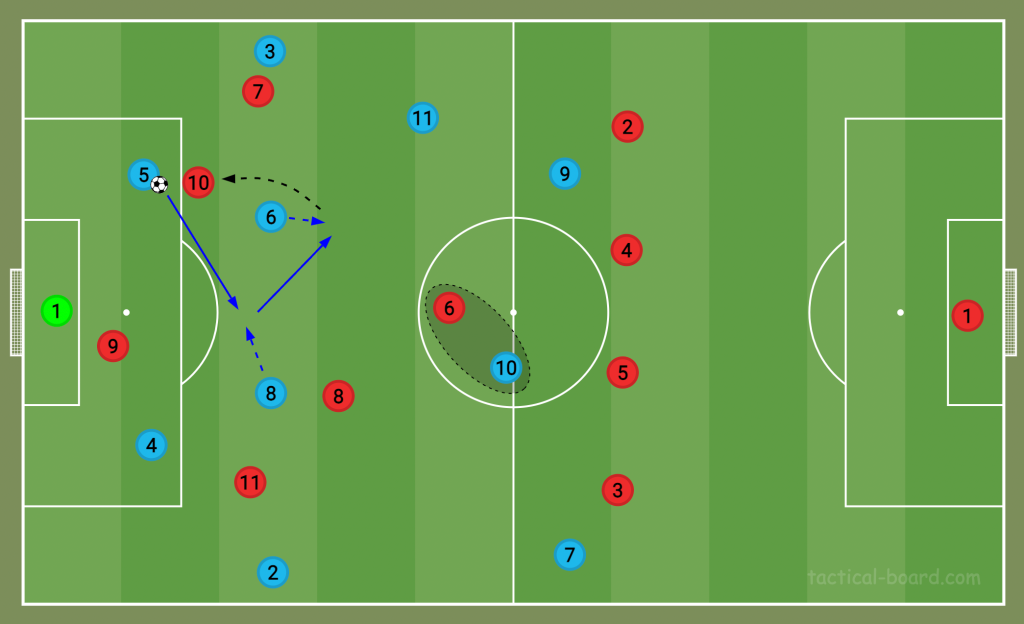

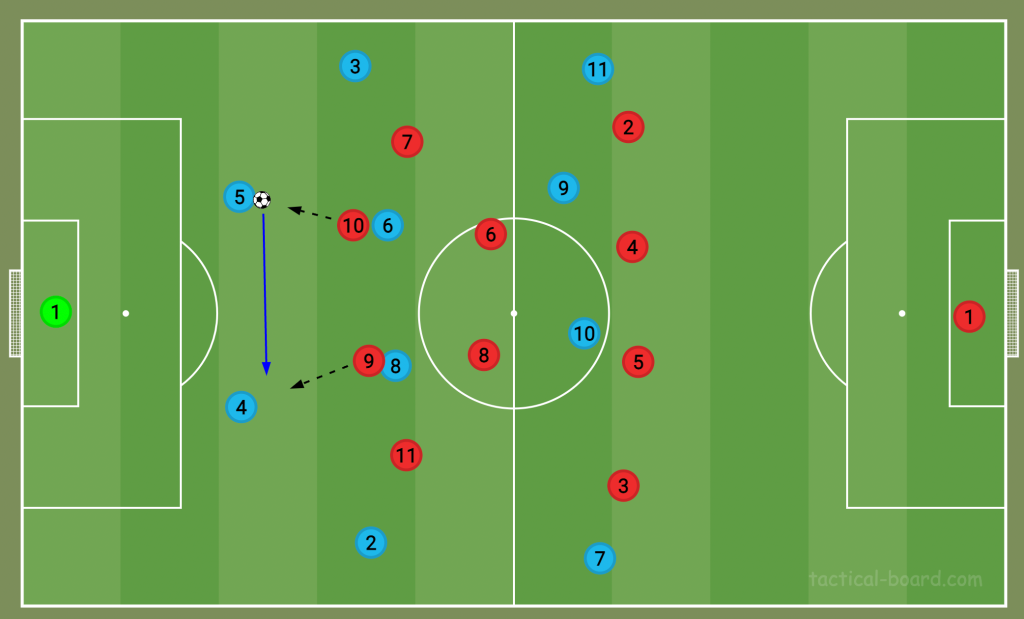

The defending team will try to shut off one side of the pitch, forcing Brighton to the other, and De Zerbi’s team usually oblige. However, their build-up aims to disrupt the positioning and shape of the defending team. Therefore, they use different movements to create problems for defending teams, like in the image below. The winger (usually Kaoru Mitoma) will drop in to make a very attractive passing option between the lines. In this specific case, the defending No10 must block the pass by pressing the centre-back and leaving his man.

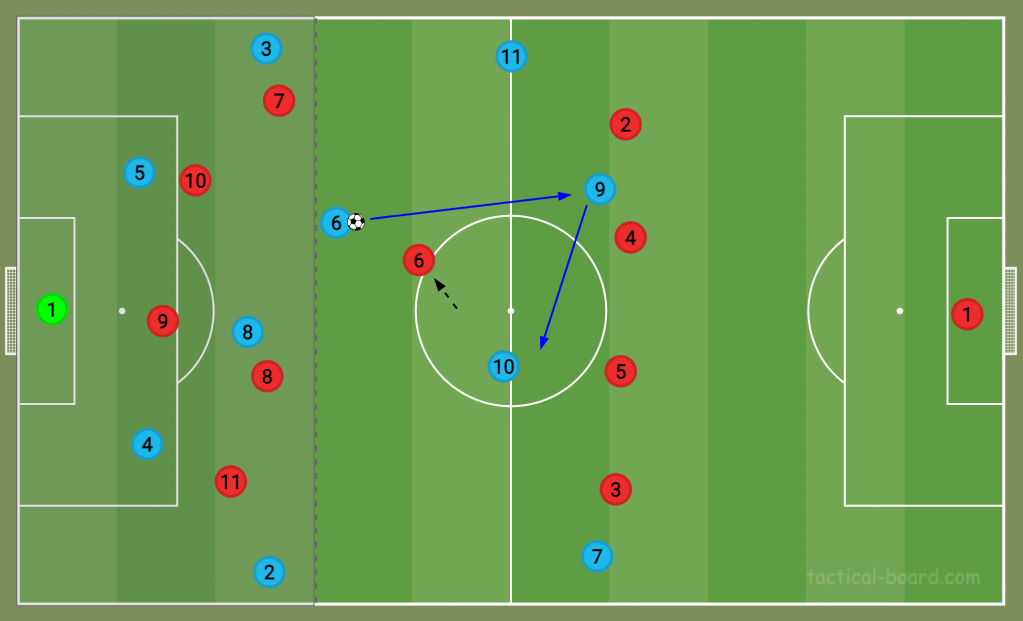

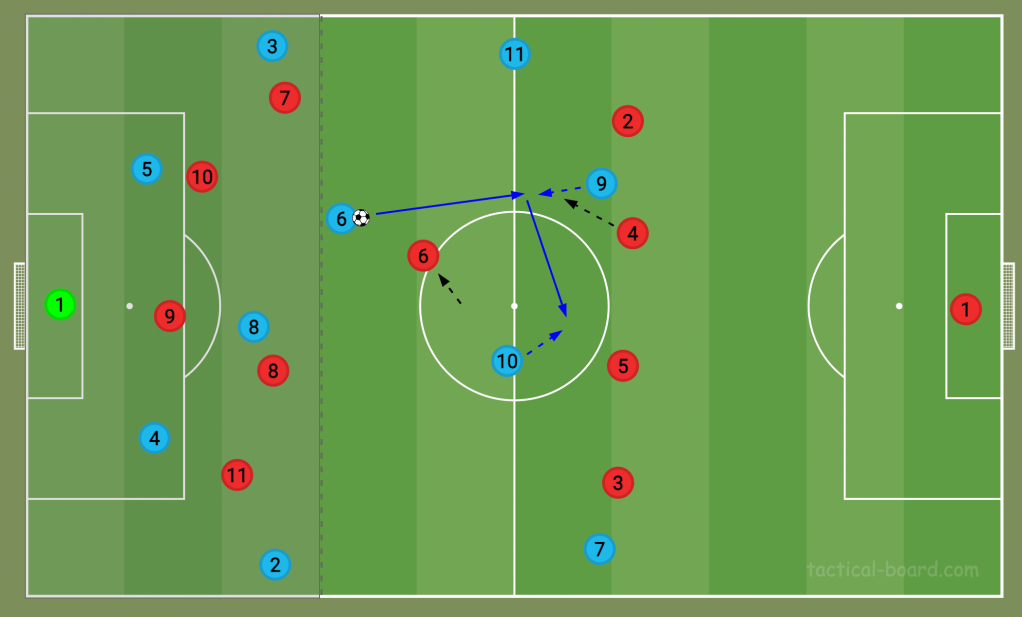

When Brighton have baited a press, and one of their defensive midfielders is no longer marked, this triggers what many people are calling the De Zerbian “S”. This unmarked pivot (No6) becomes the desirable target, but the pass is blocked. The onus is on the other pivot (No8) to run towards the centre-back, receive a pass and knock it to their fellow pivot first time. Yes, they’d be doing this while marked, but only from the south-side (behind them). Playing the ball with just one touch will avoid being tackled from behind.

When they execute this well, Brighton often find themselves in a five-v-five or five-v-four further up the field, and possession build-up can be turned into a counter-attack simply by baiting a press from the opposition.

It’s important to note that intricate spacing is key here. Caicedo and Mac Allister must be staggered to find each other in the break-out space. Both are excellent at receiving the ball under pressure, and Mac Allister, in particular, also thrives off third-man runs. This staggering is what creates the De Zerbian “S”.

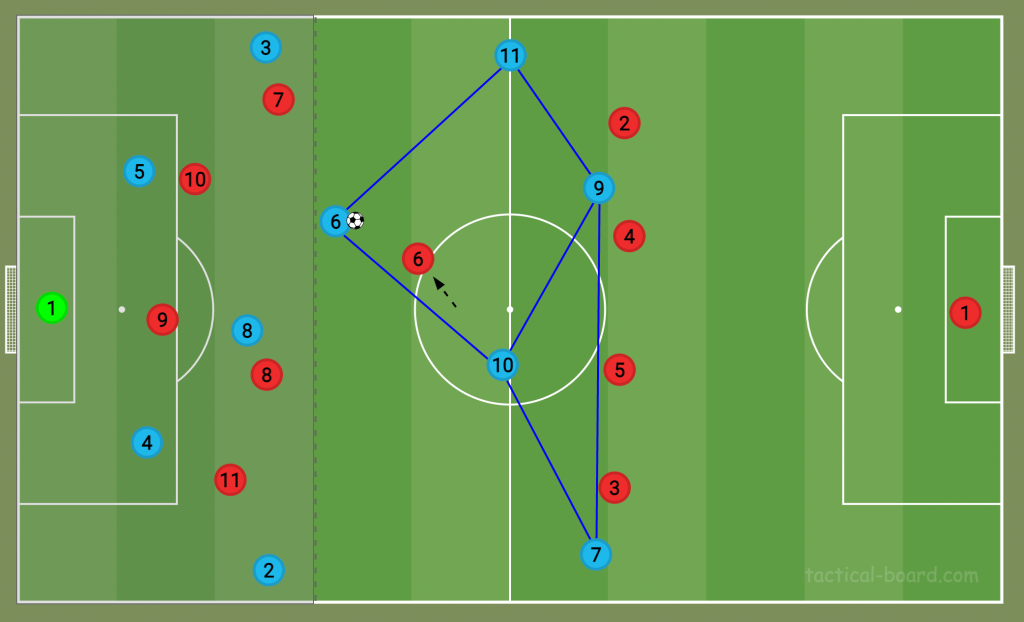

These triangles where they can find the free man occur all over the pitch for Brighton, not just in build-up. And what’s interesting is the precision of thought from De Zerbi and his team. To find the spare man, they won’t just use a third man for a triangle. The weight-of-pass is deliberately light. This means the recipient has to move towards the pass first, dragging a defender with him, before playing it to the spare man. The advantage is obvious when the triangle is complete: not only have they found an unmarked teammate, but they’ve also generated more space by eliminating an opponent from the game (they’re now behind the ball because they tracked the run).

One final thing we haven’t covered is how they always bait the press, besides having runners off the ball like Mitoma dropping in. Well, this is a straightforward two-step process. When the centre-backs have possession, they like to be very casual, often putting their foot on the ball. Levi Colwill can be excellent here. This frustrates pressing teams, who usually cave in and chase the ball to provoke a reaction.

Step two is simply to pass the ball. However, De Zerbi’s centre-backs will play a ‘square ball’. This means a straight lateral pass to the fellow defender, in this case, to Lewis Dunk. Square balls are notoriously a manager’s nightmare. Huge efforts are made in academies to teach players not to play square balls, as they put you in danger as the possession team. However, De Zerbi wants Brighton to play square balls because he knows it’ll bait a press.

So Brighton like to bait a press within their central build-up box before using triangles and the De Zerbian “S” to allow their pivots to receive the ball facing forward. It helps them keep the ball better, and launch quicker attacks.