4-3-3 has ruled the land for over a decade now, and in attack this usually makes what we now know as the 2-3-5. However, in a romantic flashback to the thoughts of Rinus Michels and Johan Cruyff, this season has seen the shape of Total Football return: the 3-box-3. When deployed by traditionally 4-3-3 sides, the only question becomes which player will move to become a fourth midfielder. Mikel Arteta has used an inverted full-back, Pep Guardiola has finally settled on pushing a centre-back up, Xavi’s Barcelona sees the left-winger invert as an auxiliary No.10. These shapes appear so similar, but in practice require completely different patterns of play. Here’s a few of their respective features:

3-Box-3:

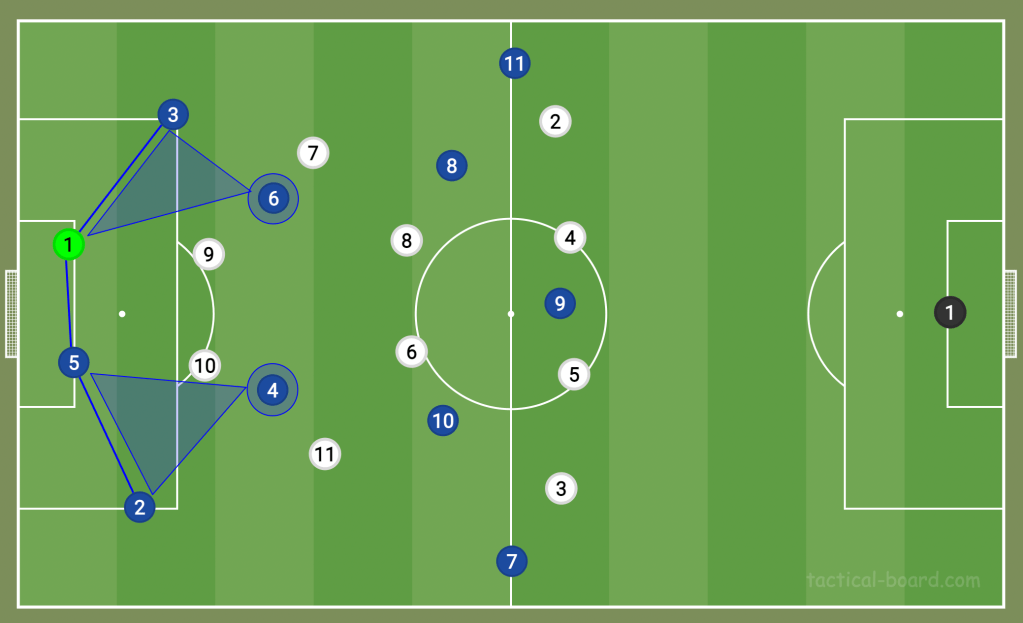

The inspiration behind the formation, when first landed on by Michels, was to maximise passing angles. Indeed, this shape is the only formation with more passing triangles than a 4-3-3 (or 2-3-5). 3-box-3 has 12, where 4-3-3 has 11.

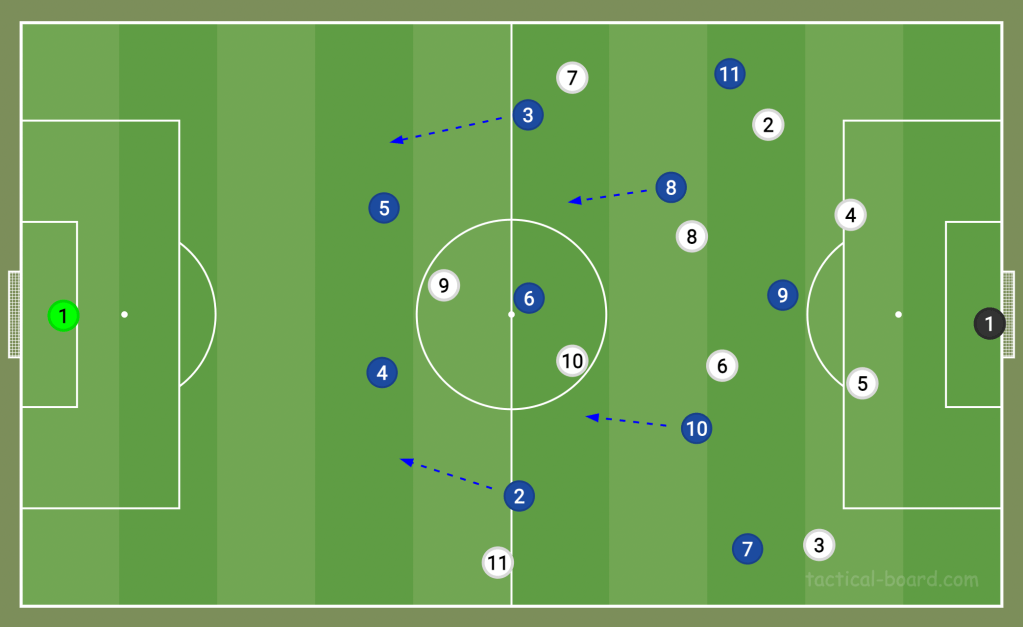

The double-pivot is very desirable in build-up too. The back-three can become a four if the goalkeeper is proficient with their feet, and with the two No.6s in front, this creates a 4+2 structure, difficult for defending teams to press against, especially since there are still two No.10s further up. The double-pivot can both engage in wide triangles to aid build-up without having to shuffle across.

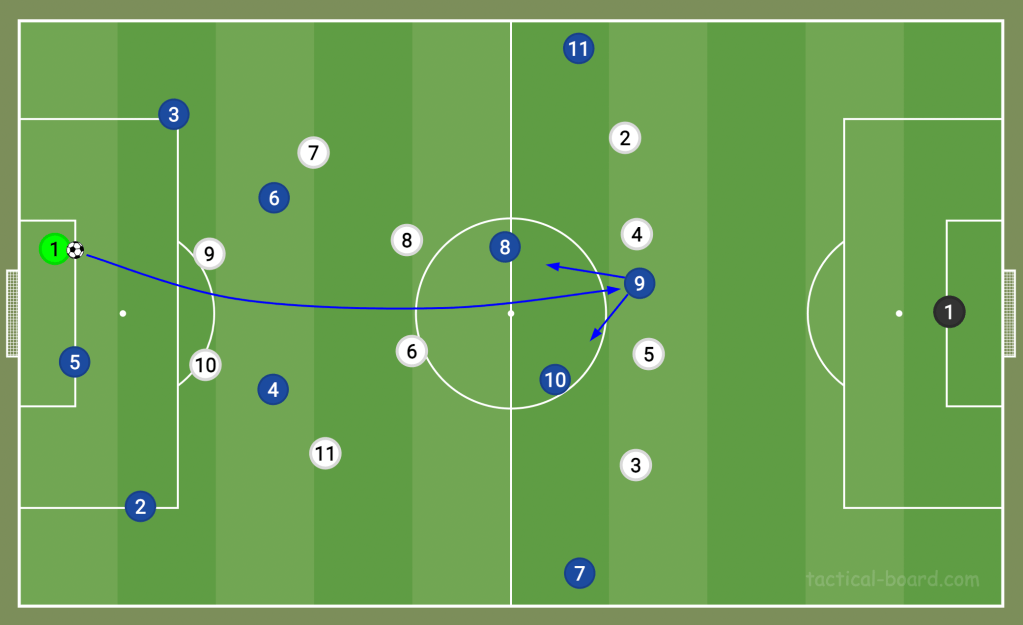

A minor feature of the 3-box-3 which rarely gets used is its perfect set-up for knock-downs. Because it’s used by teams who want to completely dominate possession, we don’t see long balls a lot. However, the two No.10s can get narrow, backing up the striker so that a long ball up to the striker can be knocked down. This takes a lot of the risk of long balls away, as there’s a fair chance they can still retain possession.

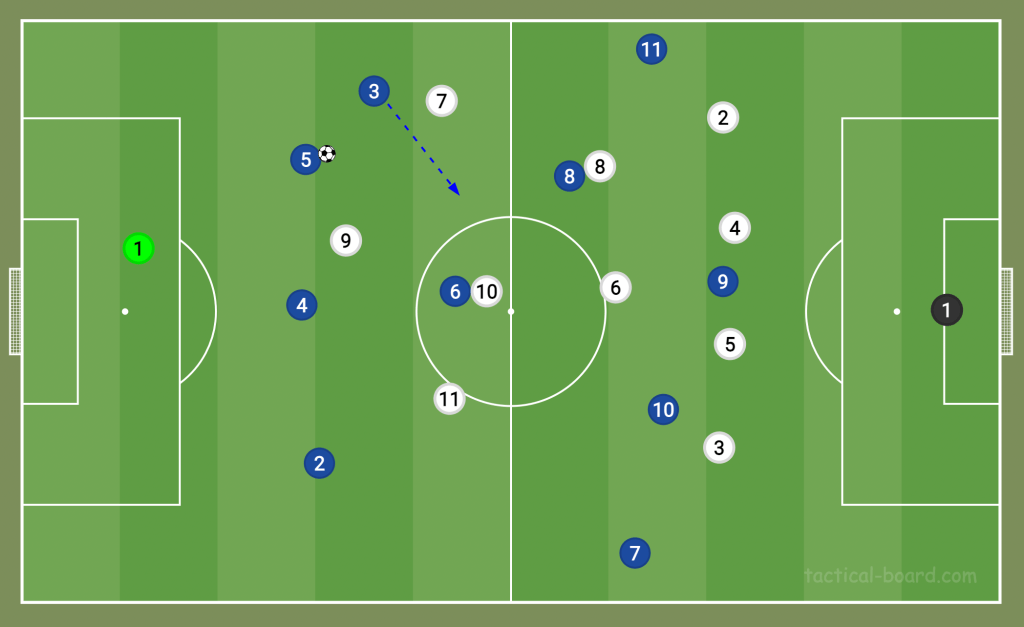

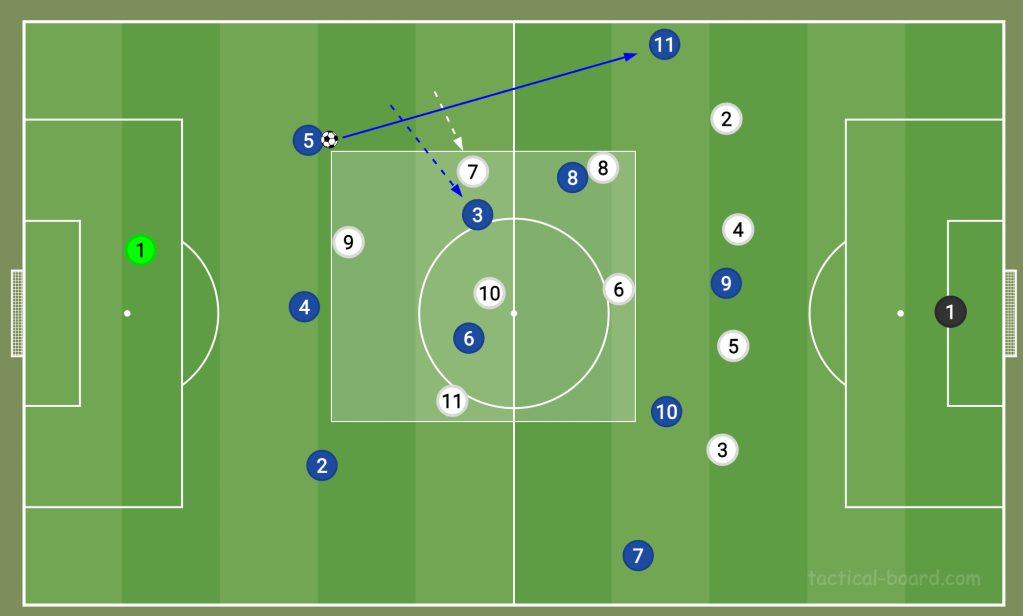

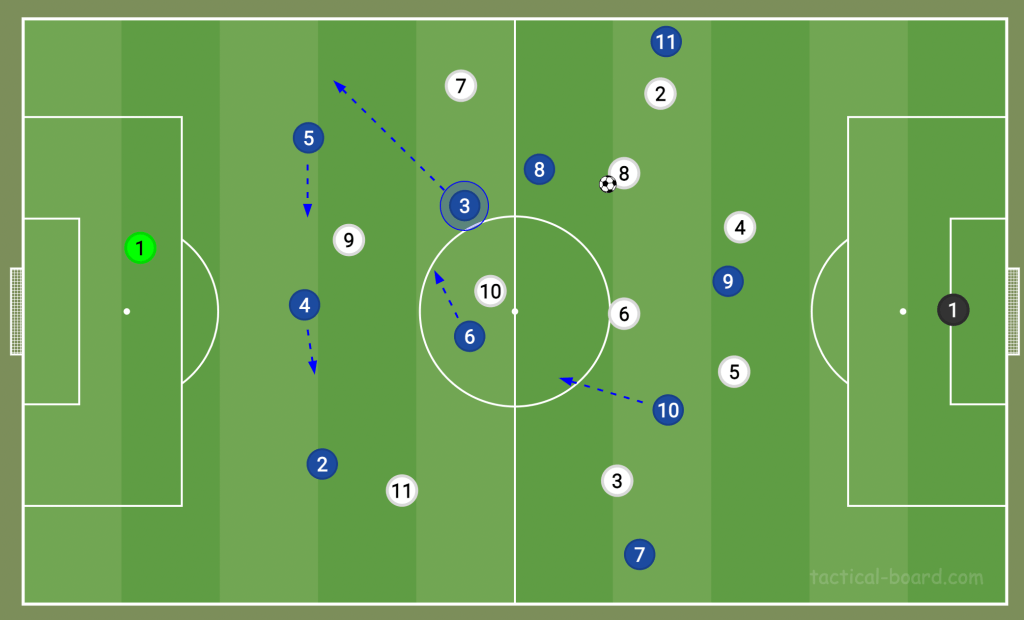

One of the most attractive features of this shape, though, is its ability to bypass an entire press. The presence of so many central players often makes opposing teams scrunch, too, including wingers. The run of the inverted full-back will drag a winger centrally, as they want to prevent a central overload. Suddenly, this opens up a passing angle from the wide centre-back to the winger. Every defending player in the white box has been bypassed, and the attacking team have created a wide one-v-one opportunity.

The chief weakness of the 3-box-3 is that this is not an attacking shape which naturally forms from a traditional, universal formation. For that reason, the teams who use it return to more conventional shapes out of possession, most often the 4-3-3. This makes attacking and defensive transitions much more complicated than in most formations, often all centred around the movement of one specific player (like John Stones, Rico Lewis, Oleksandr Zinchenko, or Gavi).

2-3-5:

Following on, the main advantage a 2-3-5 has over 3-box-3 is far simpler transitions. The full-backs retreat to form a flat back-four, and everyone follows.

In build-up, the 2-3-5 has just one No.6 pivot player, meaning to form the same triangles seen above, this player must shuffle in tandem with the movement of the ball. The No.6 is involved in more passing triangles than any player on the pitch. Teams who use this shape often have a stand-out player in their No.6, like Declan Rice and Joshua Kimmich.

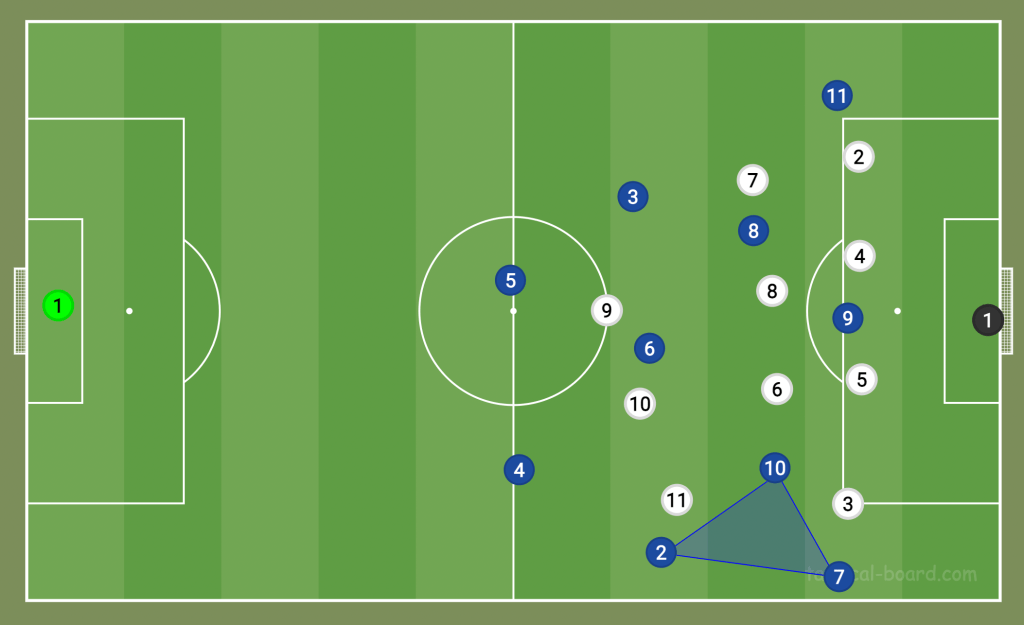

Once in the final third, a team using 2-3-5 can make easy wide overloads. The full-back has licence to push up and assist the winger. Even if the defending side double up on the flank, the roaming CM can pull wide to make a three-v-two triangle.

Unlike in the 3-box-3, a striker has much more room to show false-9 qualities in a 2-3-5 because the No.10 zone is not occupied by anyone. We see players like Harry Kane (for England) and Cody Gakpo drop in to allow the wingers to make runs in behind, creating a momentary midfield-four.