The dust has settled after England’s record-breaking summer at U21 level, but that doesn’t mean all attention has moved away from their achievement. They successfully navigated a European Championship campaign by winning six games without needing penalties and without having conceded a single goal.

It’s safe to say, at senior level, no European champions have done anything like this. The Spanish team of 2012 conceded just one goal, but even they drew two of their six matches.

The difficult conundrum with this England team is they didn’t have one or two stand-out players, but around 16 whom everyone thought had to make the starting line-up. So how did Lee Carsley do it?

The answer: 4-4-2. Back to basics for English football. Yet, this wasn’t the 4-4-2 English football is used to. This was fluid, thanks to constant and unpredictable rotations all over the pitch. Let’s break it down.

Why 4-4-2?

Given the sorts of midfield options Carsley simply had to include in his team (Curtis Jones etc.) and the lack of a defensive midfielder of the same quality and importance to the team, the logical solution was to play with a double-pivot of two typically more advanced midfielders helping one another out in a deeper role.

Jones was accompanied by the short, somewhat meek-looking Angel Gomes — who went on to control the tempo of play in every game.

Additionally, James Garner, one of the traditional defensive midfielders in the squad, was selected to play as an inverted right-back to give England a secret man advantage in midfield during attacks. Levi Colwill, at centre-back, likes to step up and address oncoming traffic by halting opposing attackers in their tracks. His success rate at winning ‘must-win’ tackles was laudable.

So double-pivot it was, and from there, it left four spots higher up to be taken by the attacking flair players. It was Carsley’s command of these higher positions, in conjunction with the full-back areas, that gave England such balance.

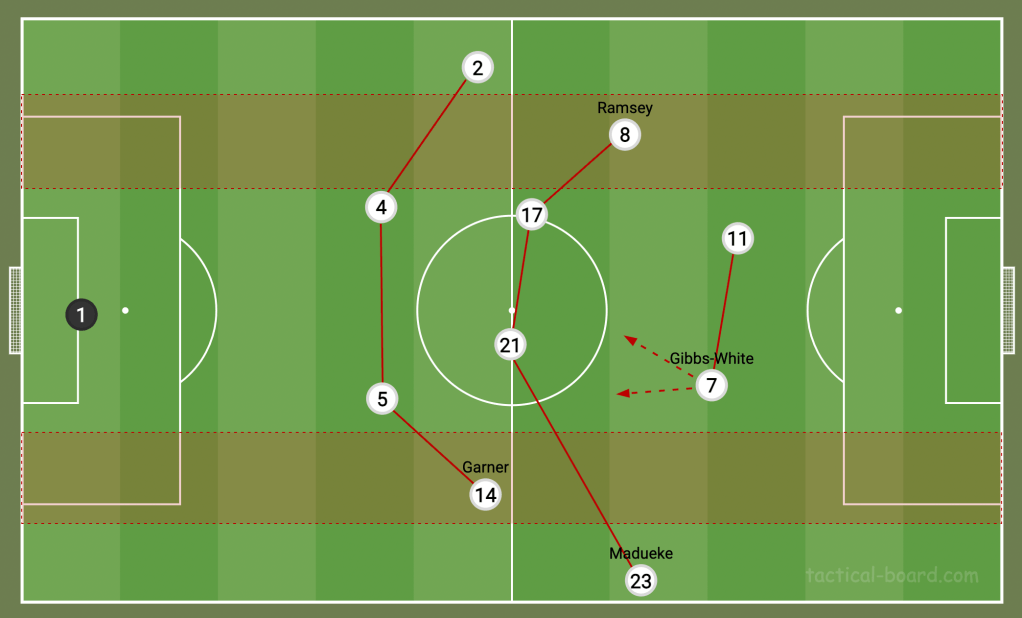

Jacob Ramsey occupied the left-midfield spot but played relatively narrow, which is precisely the role he plays at Aston Villa, even down to the formation around him. On the other side began Noni Madueke, a dazzling touchline winger who’s better at stretching the play. Behind him, James Garner played inside as a narrow full-back, while Max Aarons on Ramsey’s side offered the width that Ramsey wouldn’t.

One of the front-two positions was handed to Morgan Gibbs-White, who only recently converted from a central midfielder to a centre-forward. With the same instructions as at his club Nottingham Forest, he would drop into midfield to create a 4-2-3-1 and link midfield to attack.

Anthony Gordon played alongside Gibbs-White in a system that didn’t have an orthodox striker. He liked to drift wide to the left, which helped England’s fluidity, and Ramsey could then run infield.

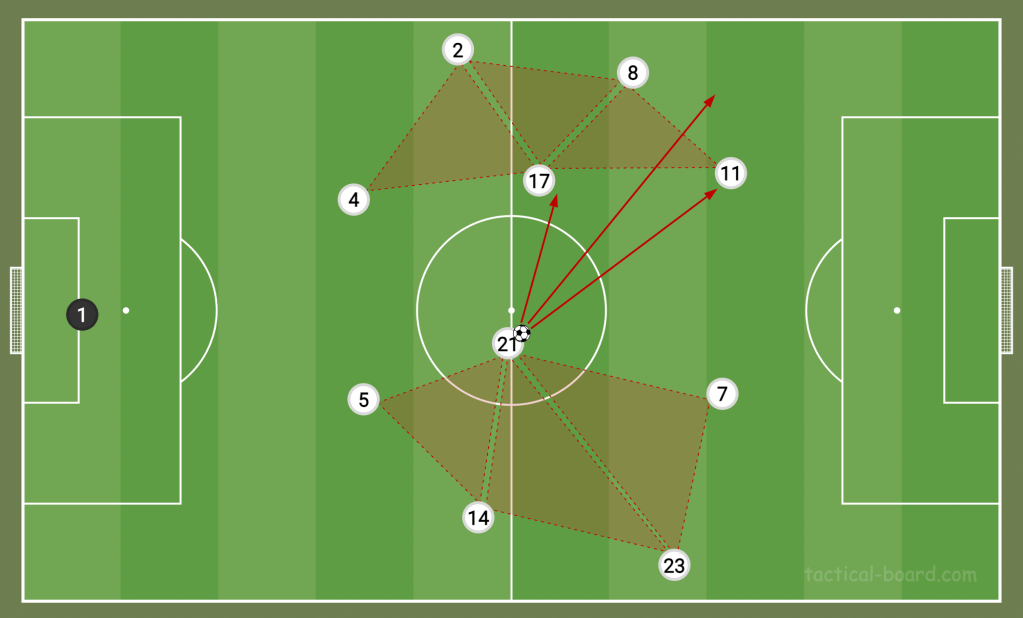

The shape could appear like a 4-2-3-1, 4-2-2-2, and in attack resembled a 2-3-5.

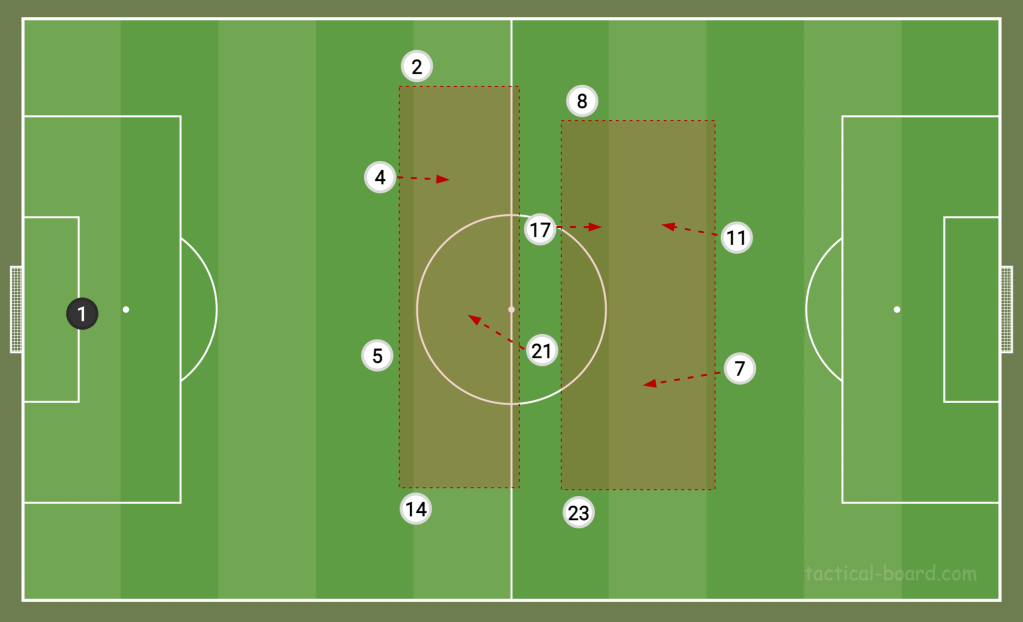

England were at their best when two or three players combined to wriggle from tight corners or blur the opposition’s structure. That’s why 4-4-2 was so helpful. It left no player one-v-one against another, and a vertical line could split the team down the middle into left and right. Within these two operations, wide triangles were easily formed. Progression and build-up play took no time at all throughout the competition for this reason. As soon as they’d made use of the link-ups, they’d find an outlet, and he’d play to the other side where the space was.

Having no nominal defensive or attacking midfielder left England’s system looking quite linear and rigid. But this was purposely done to lure the opposition out of these areas (where there was seemingly no danger) before the likes of Gibbs-White would dart back to pick up a clever and desirable area between the lines.

Off the ball, they wanted to press with a 4-4-2. This meant transitions were really simple and quick.

Notes:

- A double-pivot was the first decision. The rest of the formation was built around that.

- The system was created to match many players’ club roles.

- No striker helped fluidity.

- Lateral partnerships and triangles were easy in 4-4-2.

- They artificially created gaps between the lines to later exploit.

- 2-3-5 in attack. It didn’t matter how.

- 4-4-2 to defend, which made transitions easy.