Liverpool are ahead of schedule. How can a team that lost their entire midfield in one summer transfer window be top of the Premier League six months on? And Liverpool’s rebuild was baffling. The new recruits included one dazzling attacking midfielder and another of the same mould. How would Jürgen Klopp keep Liverpool’s identity while concealing the blatant defensive weaknesses in a midfield three of Alexis Mac Allister, Dominik Szoboszlai and Curtis Jones?

Easy, wasn’t it? There are two parts to it. First, he added another player to the midfield: right-back Trent Alexander-Arnold. With Alexander-Arnold as the fourth midfielder, they could exploit the benefits of two ‘acting’ deep midfielders to replace their previous, more traditional pivot midfielder, Fabinho.

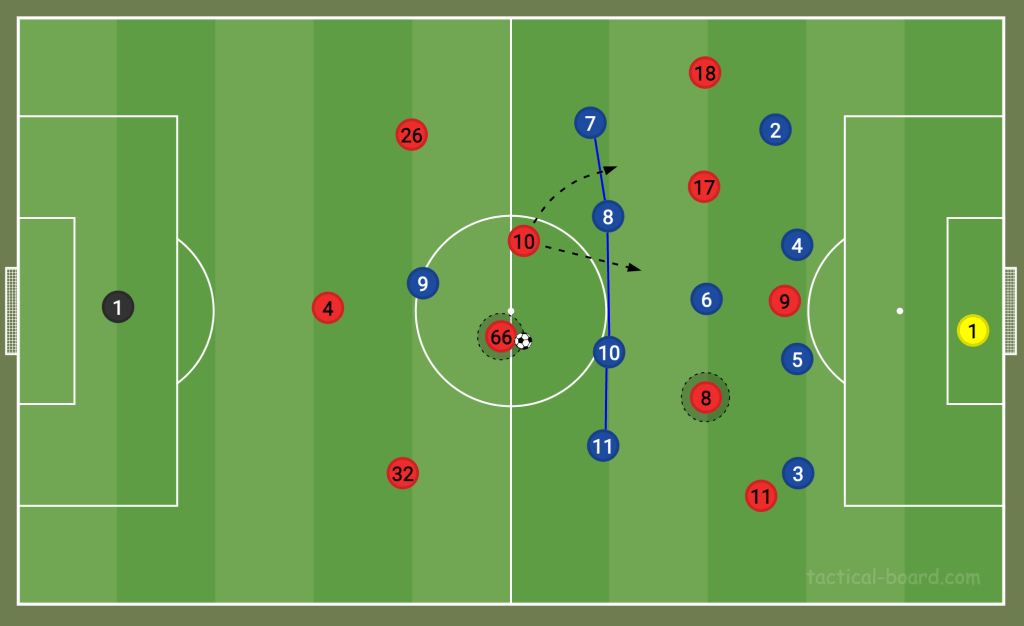

For the second part, Klopp made his midfield far more athletic than it used to be. Why? Well, all the other teams playing this new 3-box-3 shape are doing so to control possession, though Liverpool are at their best when they get runners in behind opposition backlines. So an athletic midfield would allow them to rotate positions more frequently to help manufacture these kinds of chances.

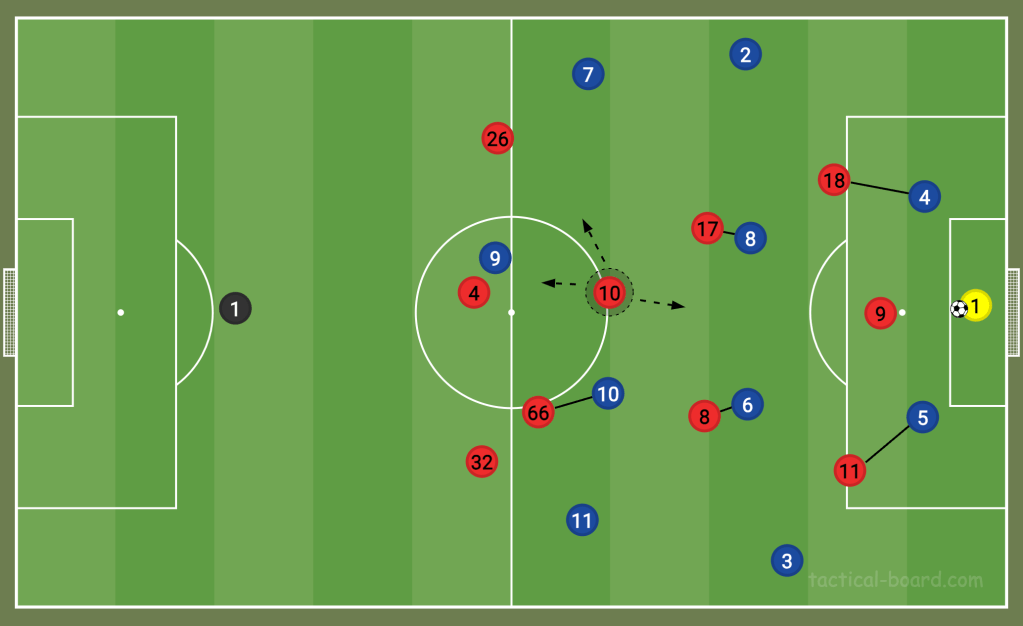

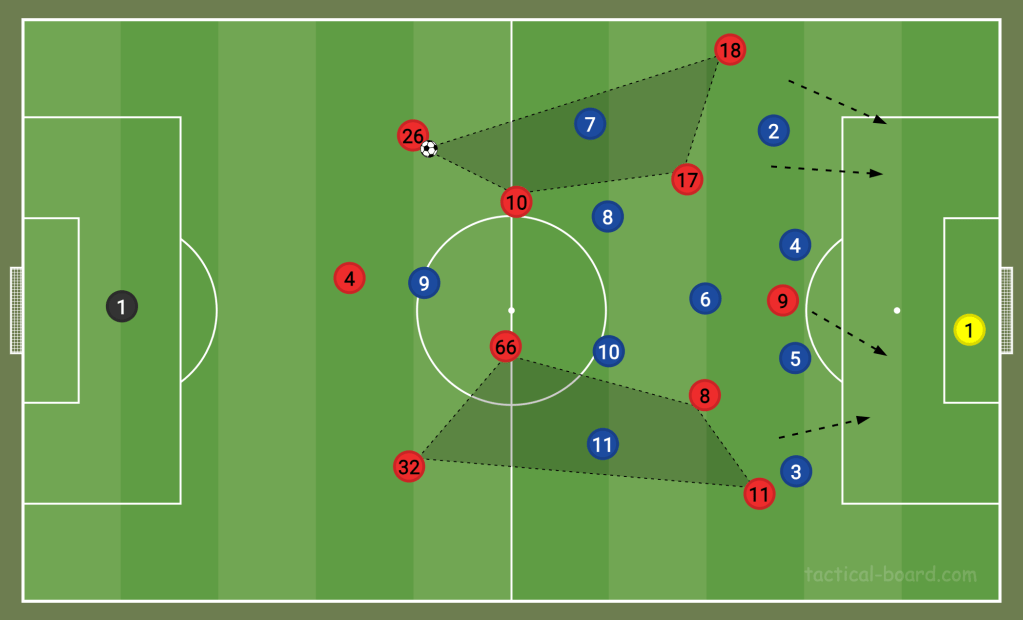

They keep this shape when they press high up the pitch, and having a double-pivot of Alexander-Arnold and Mac Allister means their two more advanced midfielders can go man-to-man with opposition players.

It makes far more sense to press man-to-man when the players are athletic, especially when the alternative (a zonal press) would mean deploying players like Mac Allister in completely unfamiliar positions.

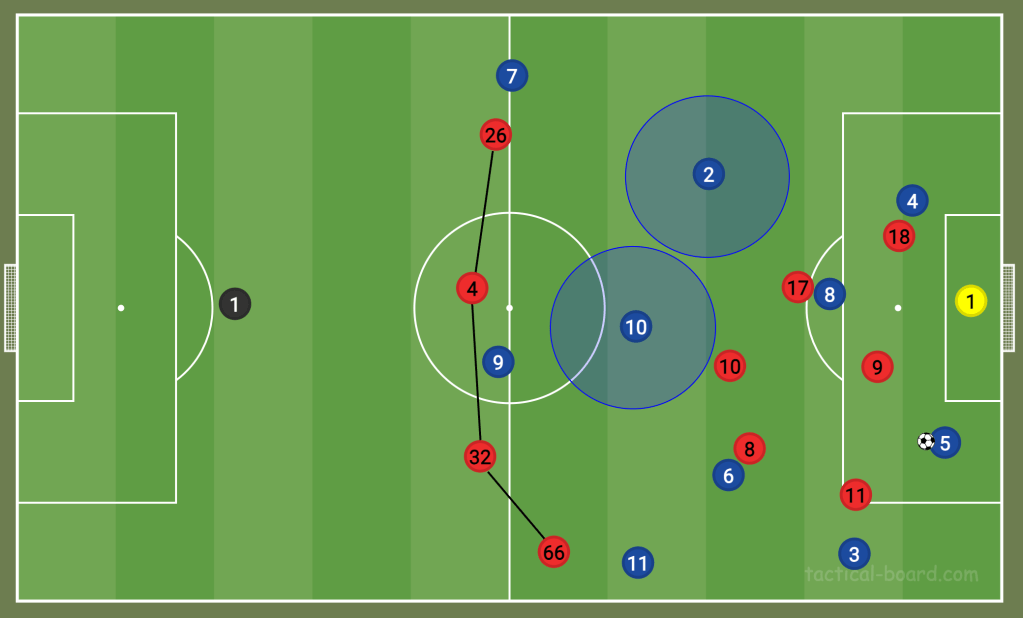

In Liverpool’s old system under Klopp, there was always the risk that their gegenpress could get bypassed by the other team, who could find players in space. However, Liverpool’s pressing shape now is particularly effective at denying space in the middle of the pitch, as they’ve got more numbers in midfield (four).

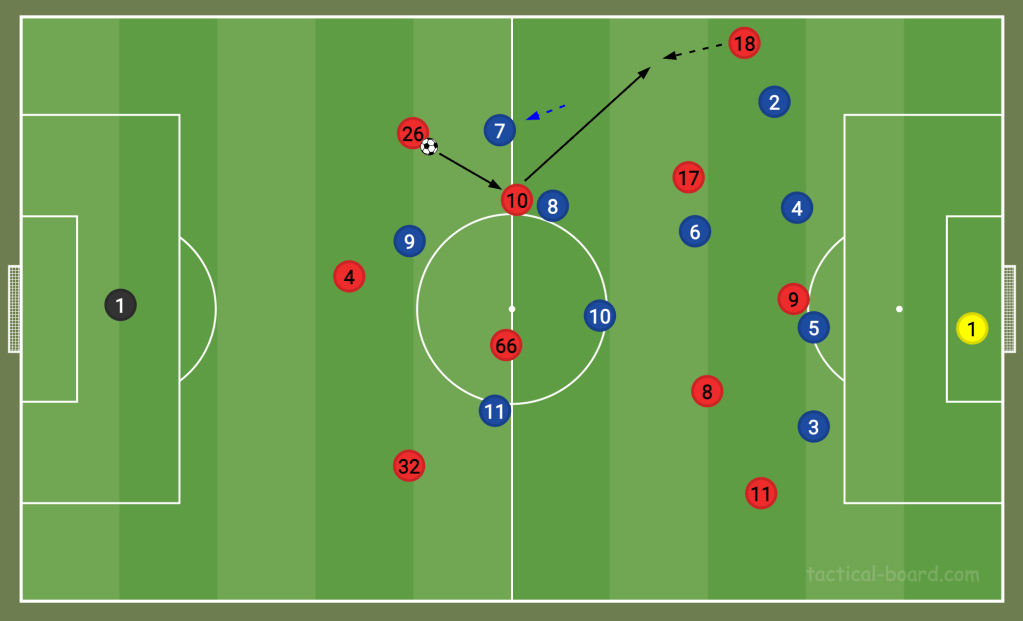

On the ball, Liverpool’s midfield has been reminiscent of Italy’s 2006 team because of the multiple playmakers in front and behind the opposition’s midfield. This has helped with ball retention and, more importantly, chance creation this year. It also frees up a player to roam wherever they please. Alexander-Arnold and Mac Allister can express themselves when the other is on the ball.

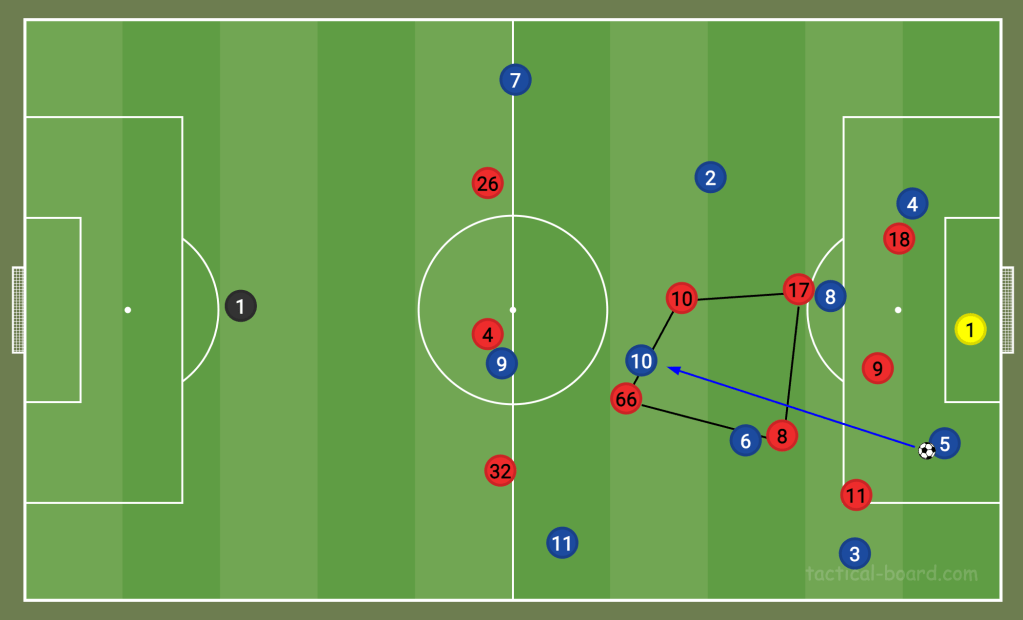

As mentioned before, Liverpool’s successes under Klopp have largely been down to their deadly fast attacks in behind defences. Their new midfield has unlocked fresh opportunities for ball progression this year. With four players committed to wide attacks on each flank, they can use clever rotations to drag other teams’ players out of position before exploiting the gaps left.

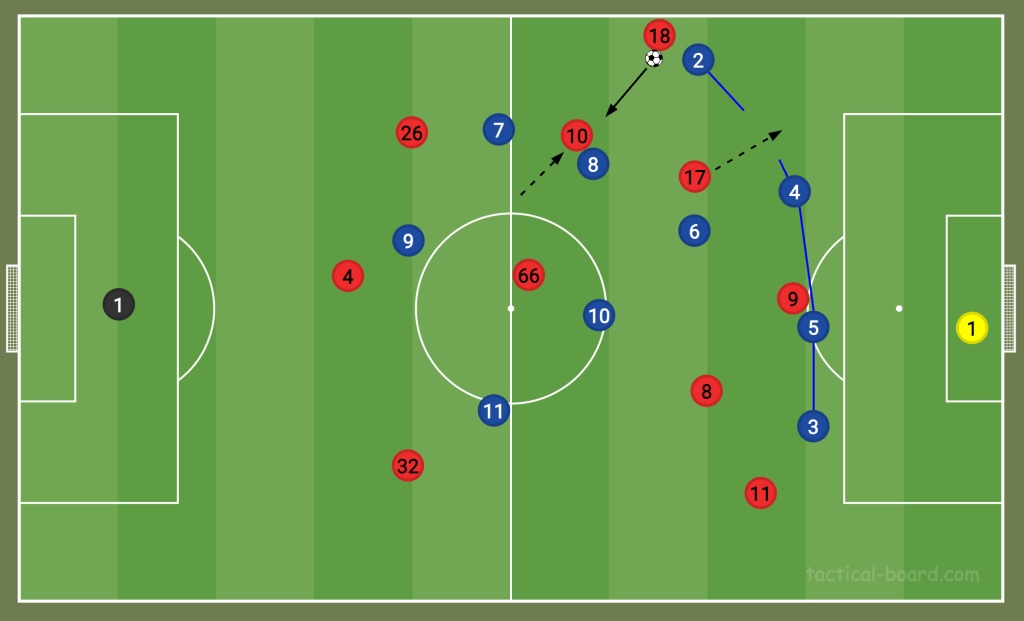

The fact Liverpool have four players in the middle of the field forces opponents to scrunch centrally, leaving more space out wide. Whereas the likes of Manchester City will instruct their attacking midfielder to drift wide and offer to receive the ball, Liverpool have enjoyed using the wingers to drop deep and drag the opposing full-back with them. We then see the midfielders running in behind where the gap has been created. Liverpool’s old midfield would rarely have done this, but it seems so appropriate that their new, athletic midfielders will make many of the attacking runs.

So this year was the beginning of a rebuild at Liverpool, and they’ve changed everything yet nothing at the same time. A complete midfield makeover has helped revitalise them, and it’s incomparable to the old Liverpool. Yet, they’re still as dangerous on the counter-attack, and their famous gegenpressing has only improved.

Have they suffered not having a traditional deep midfielder? No. Incredibly, it seems between Mac Allister and Alexander-Arnold, they’ve got what they need to play the football they want. Of all the attacking, defensive and transitional phases to analyse in football, there might only be one or two where Klopp would prefer to have a Fabinho-type player again. Liverpool are doing things their way, and with this hyper-attacking midfield, they appear as likely to win the Premier League as anyone.