For the first time since 2006, the Men’s Ballon d’Or trophy has gone to a defensive-minded player. There’s an irony in the fact that world football seems to be showing a greater appreciation for ‘pivot’ players, despite there being relatively few who can control a football match at this point in time. Rodri can.

Of Europe’s top sides, not many have a pivot as good as they ought to. Bayern Munich have João Palhinha, Real Madrid have Aurélien Tchouaméni, Liverpool have no one and Arsenal have four because none of them quite meet the standard, individually.

Rewind five or 10 years, and football games were won by N’Golo Kante and Sergio Busquets. Go back another five or 10, and we had Andrea Pirlo, Xabi Alonso and Patrick Vieira, who could do no wrong. The world has a vacancy to be filled in holding midfield, and Rodri is the only one doing it.

Many of today’s so-called ‘holding midfielders’ are converted defenders and attacking midfield players, like Declan Rice, Joshua Kimmich and Alexis Mac Allister. What we usually find is they can meet most of the criteria to play as the No.6, but crucially not all.

The first of Rodri’s real strengths is his ability to receive the ball in tight spaces. He’s what modern football would call ‘press resistant’. Happy to hold his position behind the opposition’s first line of pressure — while often being marked too, Rodri will receive a pass with his back to the goal. Having scanned for danger, he’ll know his surroundings and therefore be comfortable with an array of possible passes and movements.

This is often the difference between aimless passing around the back and beating the press. Those who have converted to playing as the No.6 from other areas of the pitch will be less familiar receiving the ball in these high-pressure positions. Some routinely pass straight backwards without even entertaining the idea of taking a risk, and others tend to wander outside of the pressure to receive the ball as a makeshift centre-back.

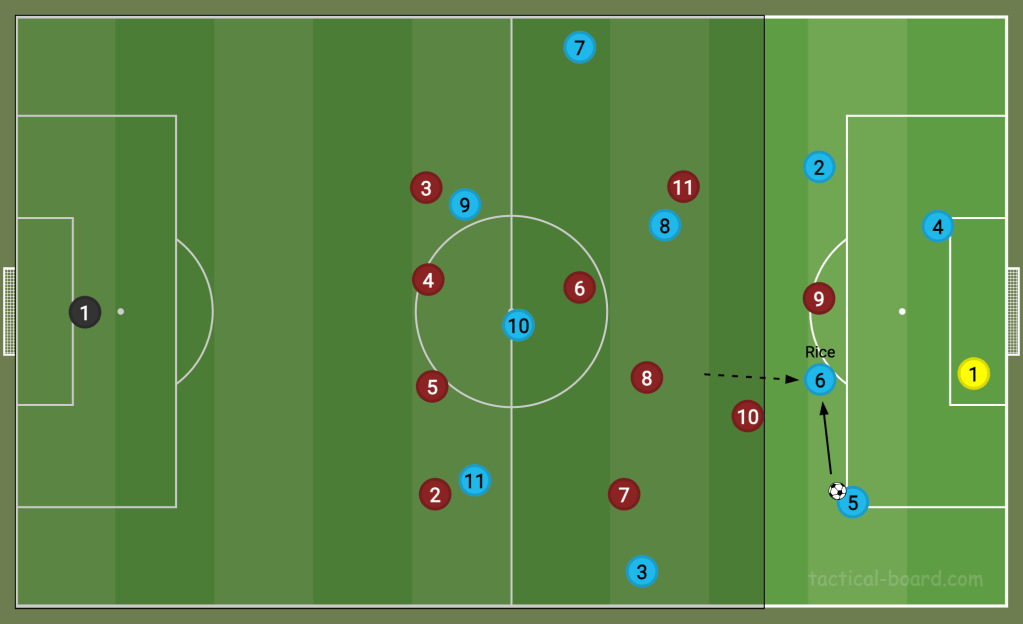

Declan Rice has often been guilty of this, and it means his teams have struggled to break through the first line of pressure… instead, playing laterally to little effect.

Playing line-breaking passes is another proficiency that should be central to any pivot player. To emphasise the point, this is, crudely, the role of a pivot player like Rodri: receive the ball behind the opposition strikers, then pass the ball through the opposition’s midfield towards the forward players.

Any No.6 who rarely plays the ball forward is one who’s contributing to aimless possession. Jorginho has been labelled a ‘sideways passer’ at times since his move to the Premier League, for instance. He’s not the only one, and it’s easy for holding midfielders to slip into easy habits, but Rodri has completed the most forward passes into the final third of any No.6 in Europe’s top five leagues since 2019.

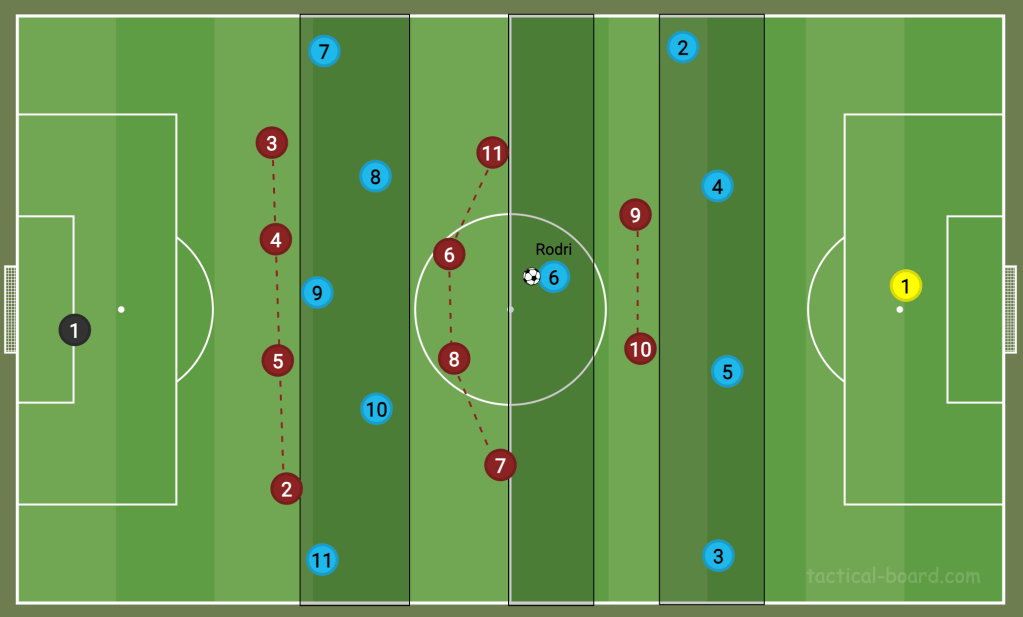

Out of possession, the primary duty of a No.6 is to simply be in the right place. Often, they’re the centrepiece of the ‘rest defence’, and it’s important that they position themselves near the danger to protect against counter attacks. Some teams adopt such high-pressing principles that they encourage the No.6 to get involved, like Newcastle with Bruno Guimarães. But it should still be down to the player to judge the situation.

This is a visual replication of a position Rodri found himself in during Spain’s European Championship quarter-final with Germany, this summer. Spain had enough players closing down the ball carrier, and Rodri needed to concern himself with the movement of Germany’s No.10, İlkay Gündoğan. Caught between two players, Rodri felt that staying close enough to the No.10 behind him — while staying connected his fellow midfielders — would give Spain the best chance of thwarting a German counter attack.

Other pivots might have opted to press high, but neglecting the No.10 behind them would simultaneously leave the defence in a dangerous four-vs-four scenario.

This relative lack of world class pivot players seems rather incongruous with football’s modern obsession over possession and control. Perhaps if there were more Rodris around, mangers wouldn’t have to overload their midfields with four or five players. Maybe that was the key to Spain’s Euro success. With Rodri the cornerstone in an excellent midfield trio, Spain could focus their attention on wide areas. They were both dominant and direct — a rare synchronicity these days.