Arne Slot has fused the direct football of Jürgen Klopp’s tenure with his own philosophies of control and risk aversion since taking over the reins at Liverpool. It’s helped them maintain their innate capacity for relentless attacking while tightening the screws defensively.

Liverpool’s tactical identity under Klopp always revolved around the full-backs, and how they were instructed to play. Slot seems to like the narrow approach, keeping his full-backs as close to the midfielders as possible. The way he sees it, the more options his full-backs have on the ball, the easier Liverpool will find it to control games.

The strange part is that the full-backs aren’t inverted in the modern interpretation of the word — moving totally into midfield to let others push on higher. Rather, they’re just like traditional full-backs, only slightly further away from the touchline.

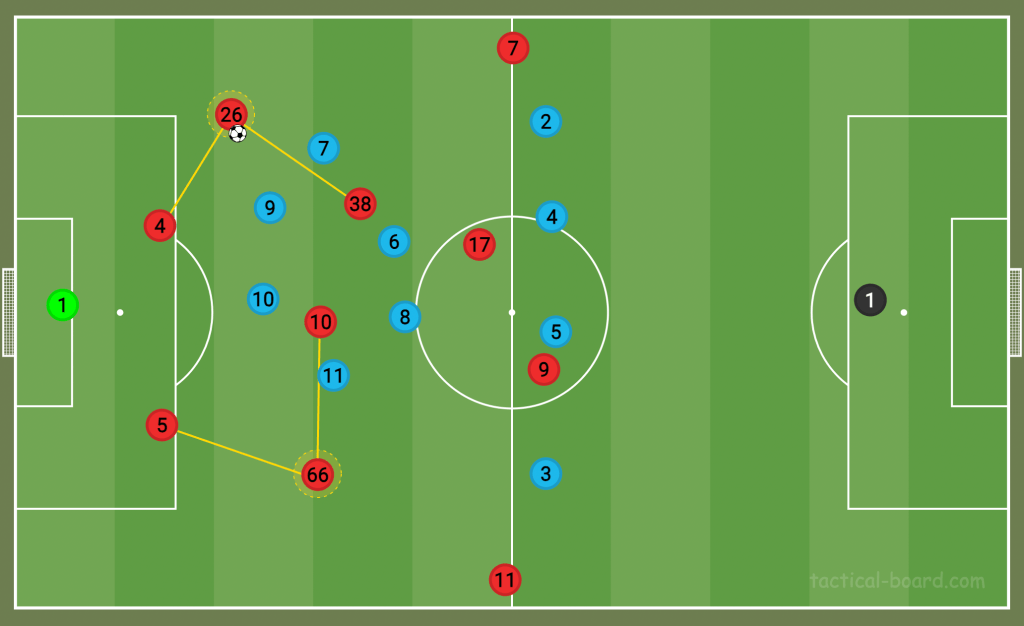

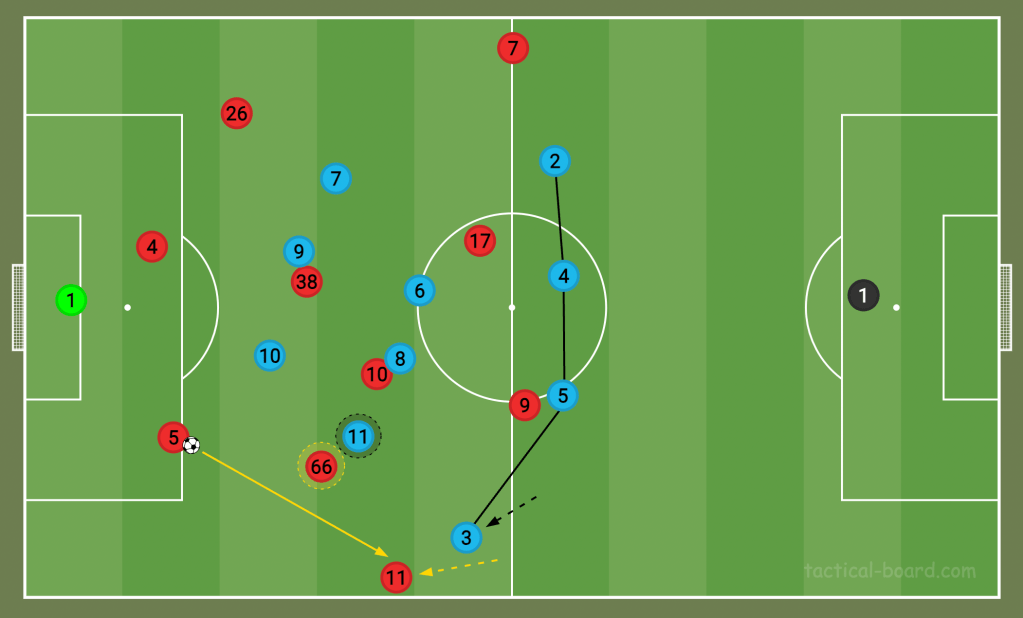

What does this mean for the opposition? They have tended to press in well-established defensive shapes — such as a 4-4-2, and have reacted the Liverpool’s narrow full-backs by adopting a narrow press themselves, with the wingers going man-to-man against Liverpool’s full-backs.

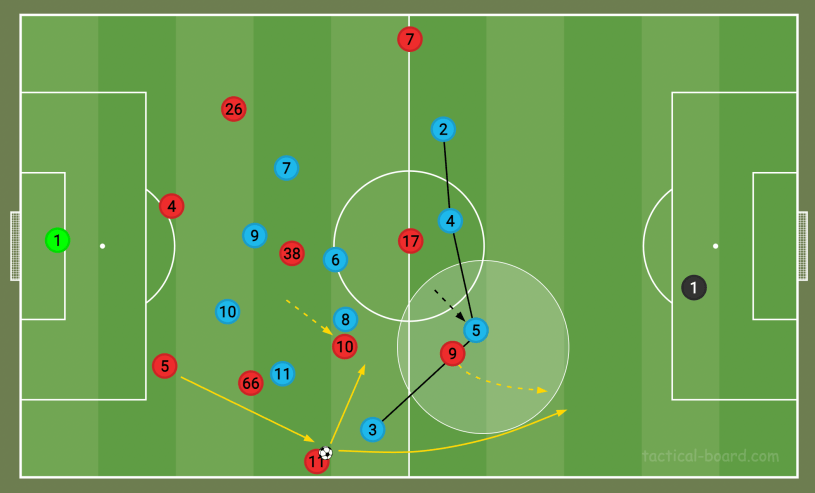

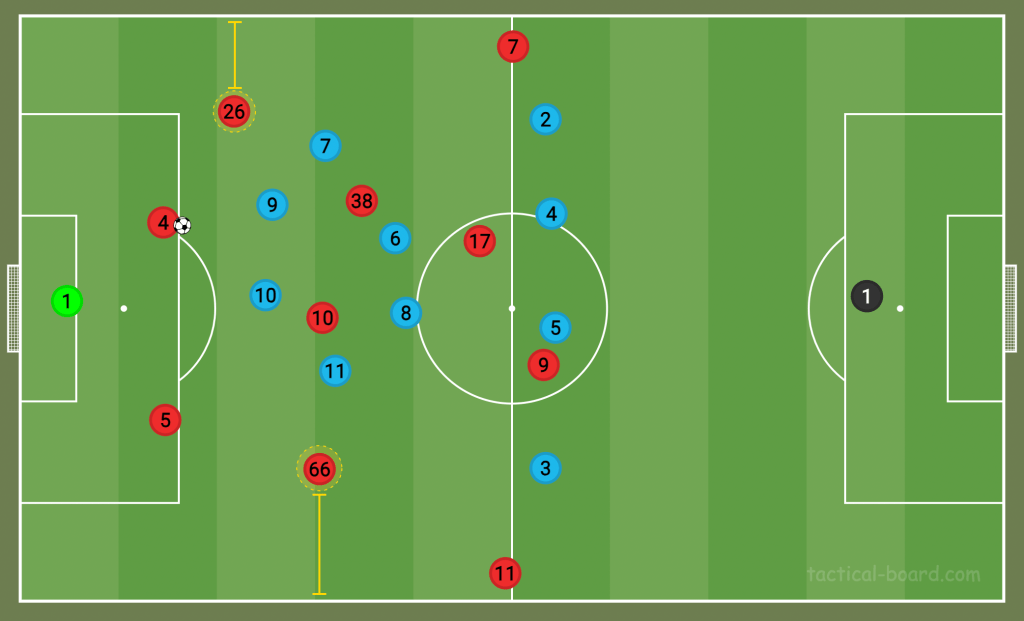

What this does mean, however, is that space often opens up in wide areas for Slot’s team to play a zipped pass from the centre-back to the winger — entirely bypassing the full-backs when they’re marked. Spectators of Tottenham Hotspur will have noticed similar patterns over the last 12 months. Very quickly, Liverpool find themselves in this sort of situation.

Because the wingers drop slightly deeper and wider to receive the pass, Liverpool’s opponents have an immediate issue. Their left-back has to engage with Liverpool’s winger, stretching the back-four further than they’d have liked.

Liverpool get the ball from centre-back to the front three so quickly (in just one pass) that their opponents don’t have time to retreat behind the ball before the right-winger makes his next move. This means when Liverpool find themselves in such situations, they’ve usually beaten the press already.

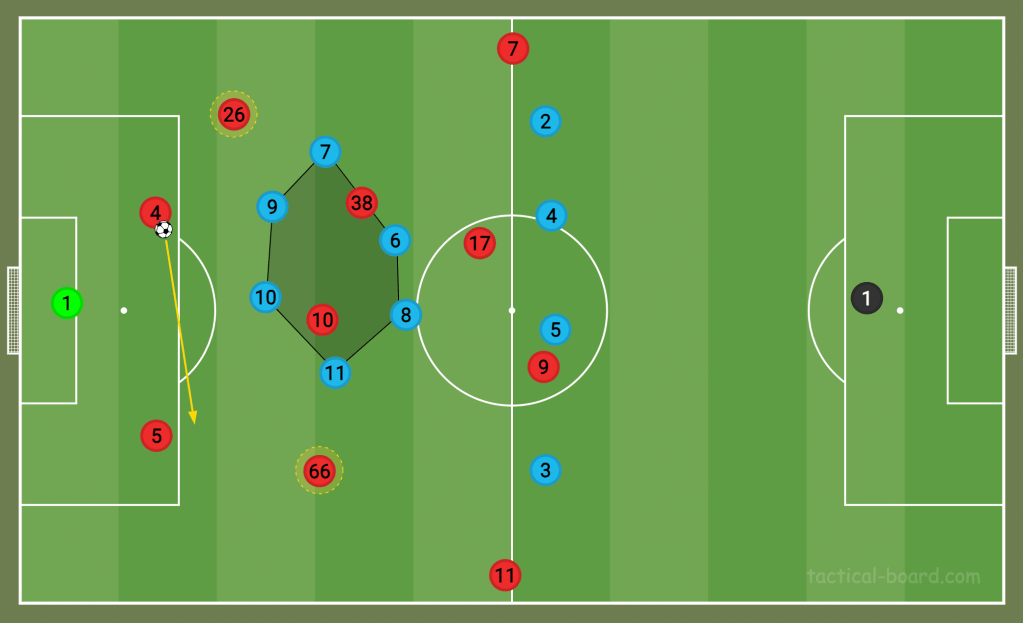

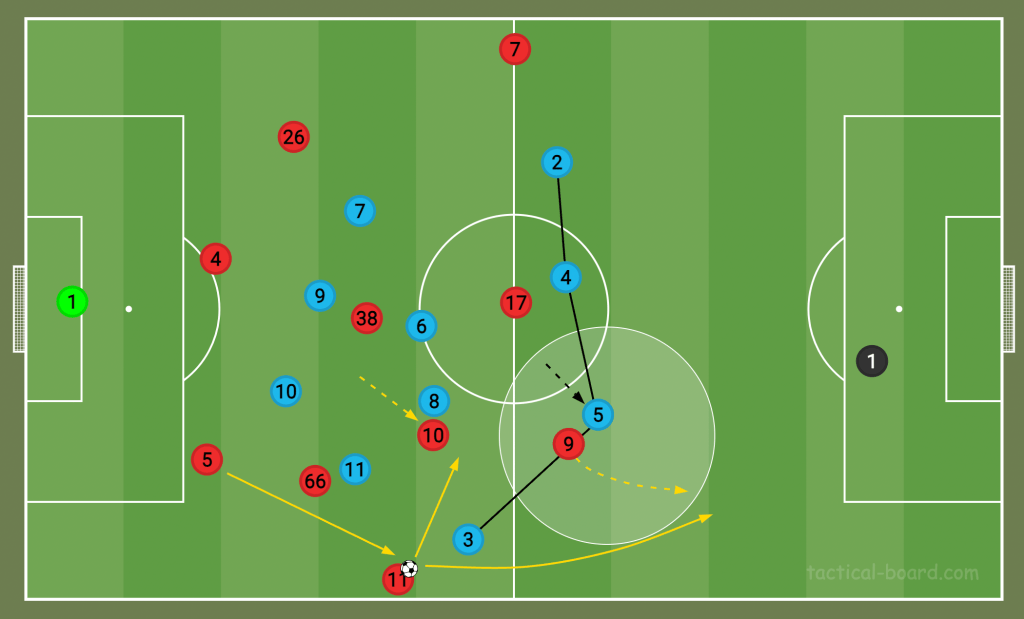

Two other important movements occur at the point when the winger receives the ball. Firstly, instead of coming short for the ball, the striker will spin in behind the defence, dragging the centre-back with him. This opens up space for Liverpool to play infield. Simultaneously, in anticipation of this, one of the deep midfielders tends to make a forward run into the hole made from the defence dropping deeper, ready to receive a pass infield.

In one pass, Liverpool play around the press, and manufacture openings infield and in behind the defence.

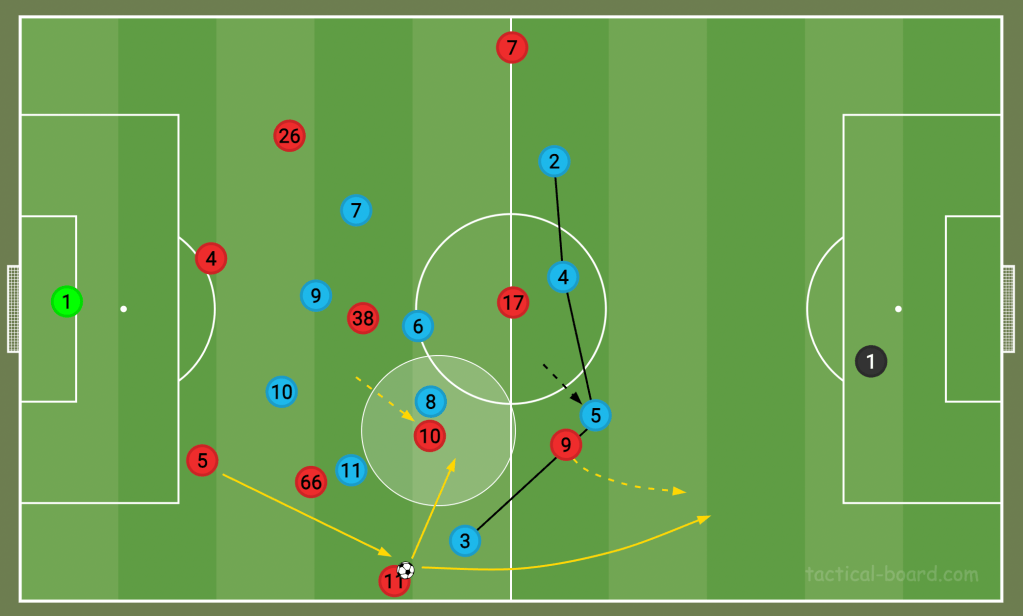

Why is this so significant? Well, more often than not, when a team players the ball from the centre-backs directly to their winger, the winger ends up trapped and forced into a backwards pass. Back-fives have proved effective in this area, but Liverpool make sure they don’t get trapped. And it’s all down to the full-backs.

You won’t find many teams setting up in a back-five against Liverpool. Why? Because it leaves them with just five other players to press Liverpool’s six-player build-up structure and worry about the attacking midfielder behind them as well. Due to the narrow positioning of Tent Alexander-Arnold and Andy Robertson, Liverpool can always play through the middle with short passes when they have a numerical advantage.

We could call Liverpool’s full-backs ‘hybrid full-backs’, because opponents don’t know whether to treat them as wide or inverted full-backs. Either way, they get punished.