Any team managed by Unai Emery will be frustrating to attack against, but since arriving in October, Emery has turned Aston Villa into a slick possession side. Sticking with his favoured 4-2-2-2 shape, he’s created a system with in-behind threats and effective use of the half-spaces, and he’s getting the best out of the players he’s got. Here’s a collection of the possession patterns we’ve come to expect from Emery’s Villa.

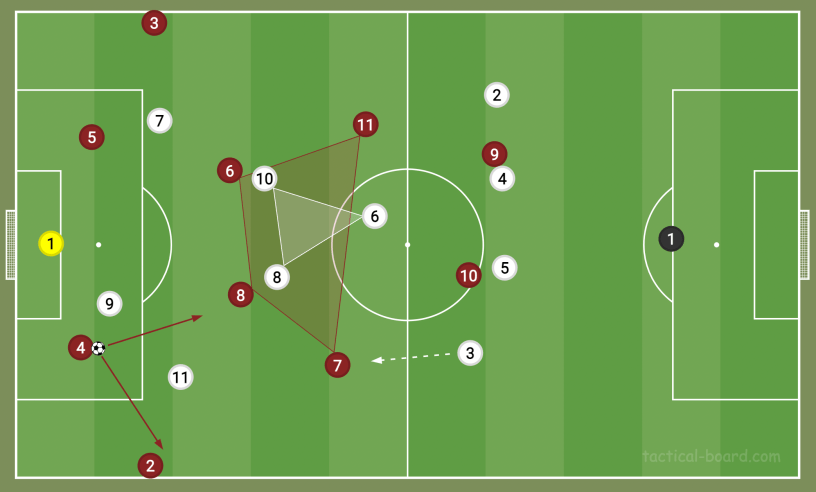

The first thing to say is that Villa show precisely how to create and deploy triangles successfully. Aided by an abundance of movement off the ball, they’re able to form triangles and squares all over the pitch. They’ve always got at least one player they can bring in to support the triangle if another shirt is needed, and there’s always an obvious outlet to make the triangle effective.

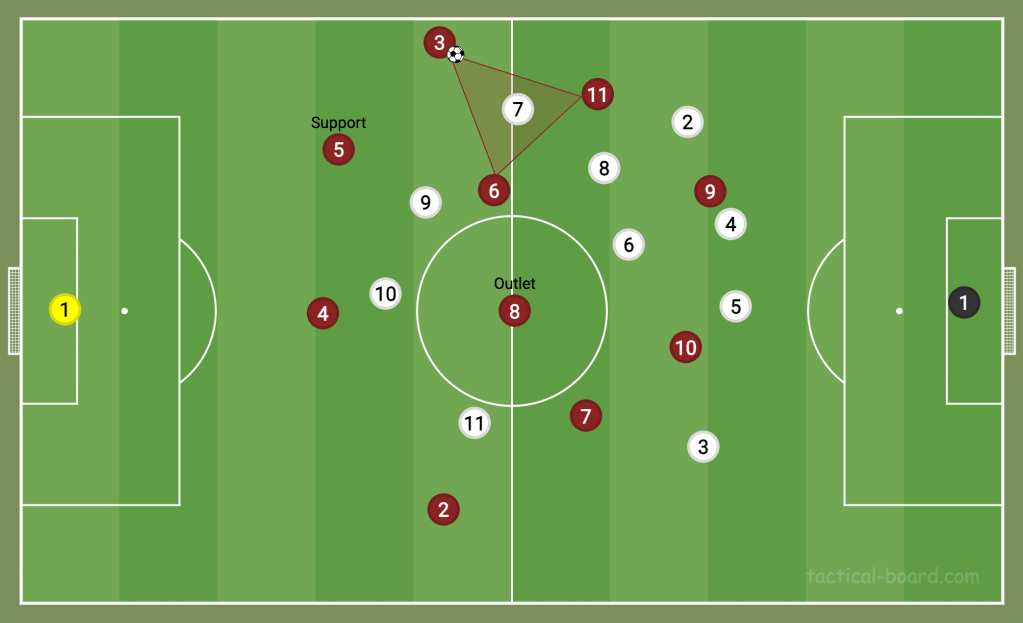

Starting from the goalkeeper, the back-four stay deep and spread wide. The two No.6s in their double-pivot are crucial to build-up, staying in close proximity at all times. This makes it hard for pressing teams to block all attacking avenues.

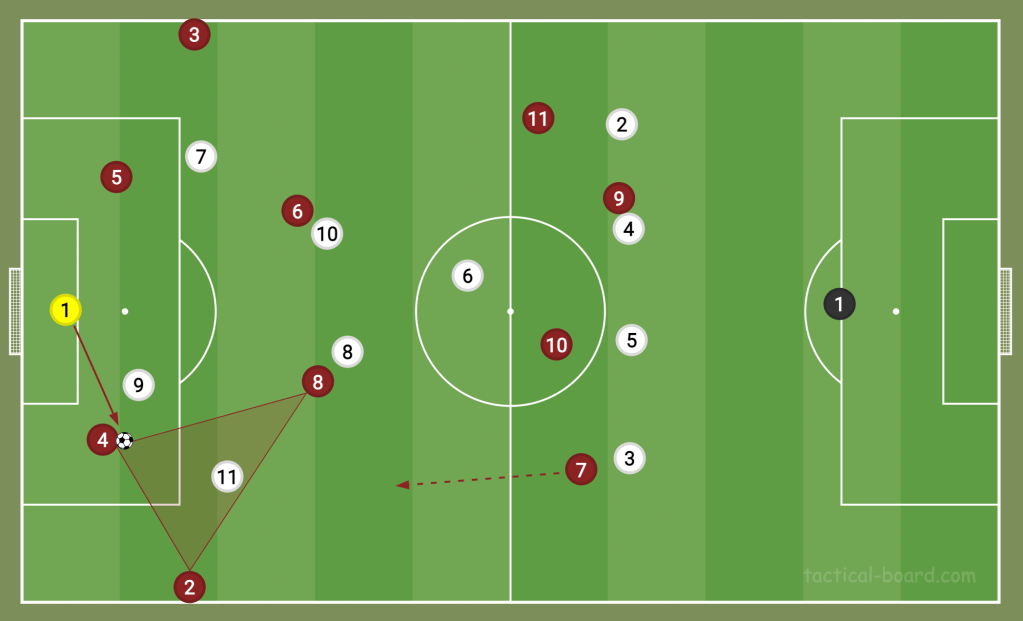

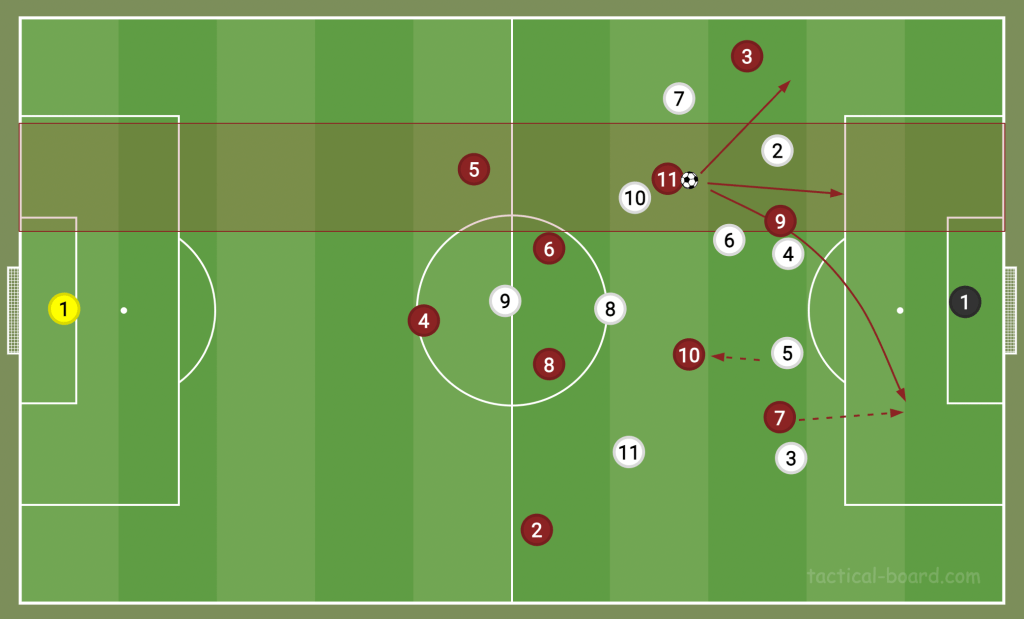

A triangle is instantly visible as soon as they commit to one direction. Villa don’t use traditional wingers but instead wide No.10s. This creates confusion for defending teams and means they’ve always got a player in the half-space. The near-side wide No.10 will peel off the back line (whom he’s been pining back) and offer himself as an outlet. This movement is notably clever and crucial to their manoeuvring of the opposition. It creates a dilemma for the opposing full-back: does he track the run or hold his shape. It’s important to note that this is a win-win situation for Villa.

If the full-back holds his shape, the narrow positioning of the wide No.10 creates a desirable midfield box from which Villa can control the centre of the field. If the full-back tracks the run, this opens space for the near-side forward to run in behind. They’ll often notice this and play the ball straight to the full-back to make this long pass easier.

If this pass isn’t on, they like to try and find the far-side No.6, who’s usually well-positioned as an outlet and often neglected as a potential threat by the opposition.

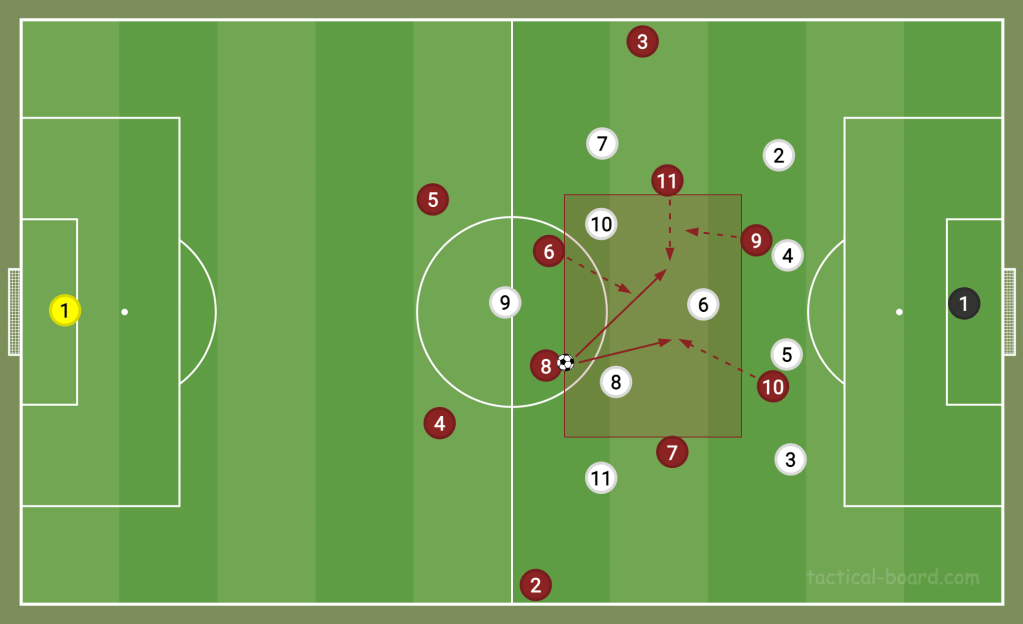

During progression in the middle third, the main appeal of Villa’s 4-2-2-2 becomes apparent. Within this shape, there’s no central No.10 player. In fact, there’s an obvious zone that Villa entirely vacate. Many teams are doing this now, and it’s part of a scheme to lull opposing teams into thinking that’s not where the danger lies. However, having different players running into this zone is less predictable than having one designated player occupying the No.10 area. Different players will dip into and out of this zone when they’re on the ball, and it’s hard to track.

What this does mean, however, is Villa have an excellent command of the half-spaces, giving them access to the flank and central lane simultaneously. Their marauding full-backs hug the touchline, and the forwards like Ollie Watkins are comfortable drifting wide as auxiliary wingers. Recently the far-side forward has dropped into the hole while the far-side wide No.10 will make a back post run for any deep crosses.

The far-side wide No.10 has become more of a winger in recent months because Emery’s opted to keep the far-side full-back back, forming a back-three rest defence when they’re attacking, since this gives them better security against counter-attacks. With the full-back deep and narrow, the onus has been on the wide No.10 to create natural width and stretch play.