Since the time of sweepers, the 5-3-2 formation has mainly been used by teams who seek to defend man-for-man against 4-3-3s and 4-2-3-1s, matching the attacking team up. It would be the job of the wider central midfielders to press opposing full-backs. However, this perhaps embodies why tactical theory can’t always be relied on.

In-game, full-backs would have far more freedom to roam wide than the defending centre-midfielders. In certain phases, the defending midfield-three would have to go man-for-man with the attacking team’s midfield-three. Therefore pulling wide to cover a full-back would leave an overload in the middle, and staying tight would allow too much room for the full-back. This, in essence, is the main issue with using a 5-3-2 to defend a 4-3-3.

However, the recent development of the 3-box-3 has seen full-backs invert like never before. Back-threes are followed up by a double-pivot, meaning natural width is detracted from build-up. This might just play into the hands of the 5-3-2 shape, which focuses on blocking central passing routes in the initial press.

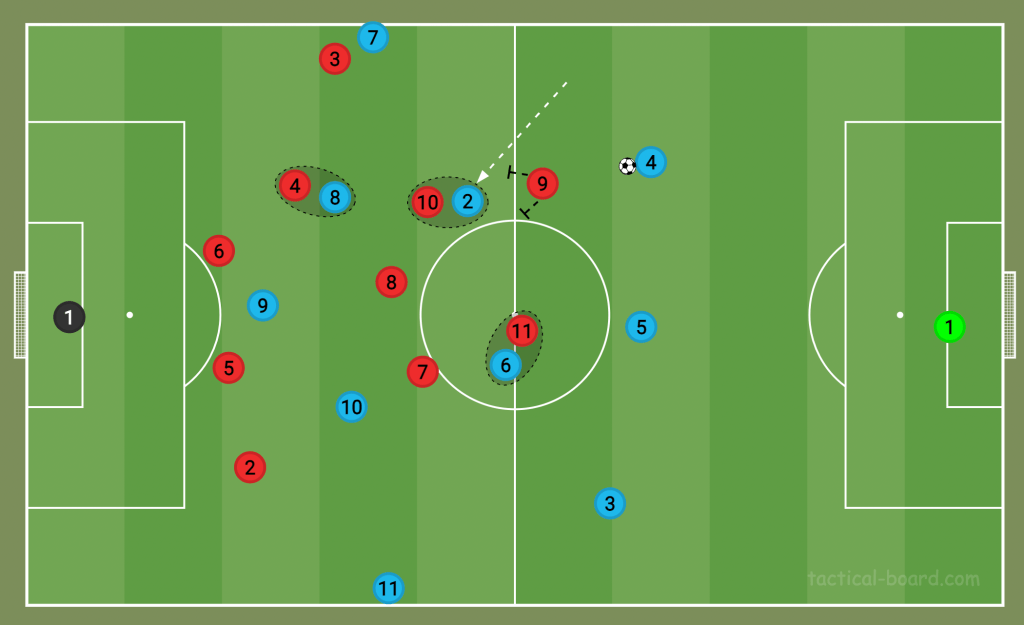

The inverted full-back in the double-pivot can be marked south-side by the centre-midfielder, while the front-two use cover shadows to mark north-side, blocking passing lanes, as seen below.

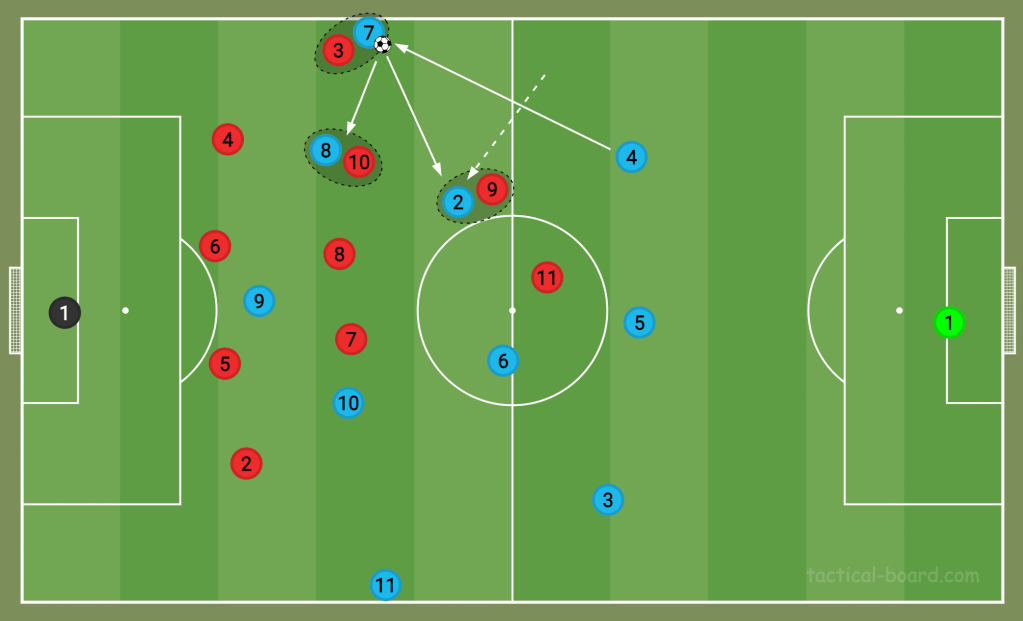

Furthermore, the 5-3-2 could use pressing traps to encourage teams to play from centre-back to a winger before blocking the winger’s potential routes infield, isolating them one-v-one with the wing-back. The remaining four defenders can also create a temporary back-four, allowing the wing-back to fully engage in the duel without checking his shoulder for third-man runs.

It’s worth noting that this only works because 3-box-3 doesn’t offer orthodox two-v-ones on the flank, so the fact that the 5-3-2 only has one wide player isn’t an issue. Of course, if teams begin to use the attacking No.10s to pull wide and create overloads, then a 5-3-2 would have to become more creative or even morph into a 5-4-1.