Crystal Palace will feel indebted to Roy Hodgson, who has twice stabilised the club from a wobbly state of limbo between ambition and pragmatism. At last, however, they seem to be taking the much-needed leap towards building something modern and exciting. Enter Oliver Glasner…

The 49-year-old Austrian coach, whose work in the Bundesliga has attracted attention and trophies, is sure to implement radical change in South London. So what should we expect from ‘Glasner-ball’?

Glasner is not a tactically dynamic coach. Instead, he’s got a clear philosophy and takes this wherever he goes: back-three, specifically 3-4-2-1, transitional football, and high intensity. This 3-4-2-1 is not dissimilar to Xabi Alonso’s emerging tactics at Bayer Leverkusen and lends itself to easy and quick transitions — something Glasner’s side will need to master in the Premier League.

The good news is Glasner’s 3-4-2-1 will not be a drastic change from the 4-2-3-1 Palace have deployed this season. A feature of their football has been wide full-backs and narrow wingers. Glasner will welcome this as he turns these full-backs into wing-backs and uses the wingers in ways they’re familiar with.

Why does Glasner love a 3-4-2-1? If you think of the formation as a narrow 3-2-3 flanked by wing-backs, the shape provides excellent opportunities to play transitional football, creating five-man overloads with the front three in attack and retreating into a back-five when defending deep.

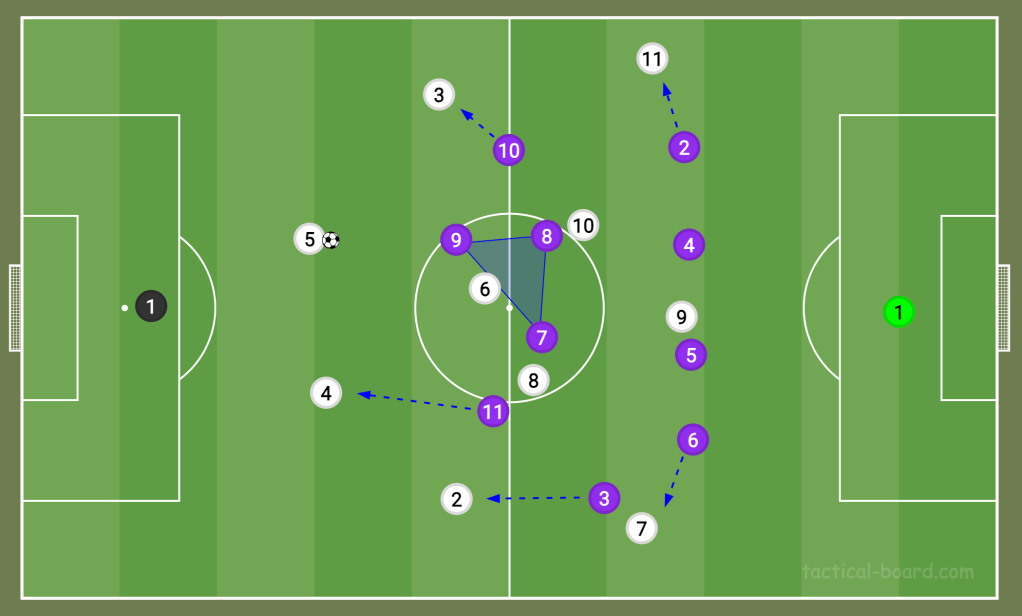

The beauty of installing narrow wingers (or wide No10s) is that while oppositions are distracted by the wide threat of the wing-backs, Glasner’s team are creating a midfield box — which has been so popular in Europe over the past 18 months. This gives them a direct attacking route out wide and a more patient, controlled attacking approach in central areas.

For this to work, however, there are conditions (as seen above). To allow the two No10s to drop into midfield roles and create this box, the wing-backs must be positioned high and wide, stretching the opposition defence. If they were not high up, no one would be pinning this defence back, and the full-backs could simply track the run of Glasner’s No10s into midfield.

As a knock-on effect, Glasner’s two outside-centre-backs have to spread wide to cover the void left by the wing-backs. Centre-backs who can fill in as auxiliary full-backs will be an essential ingredient for Crystal Palace under Glasner. This only adds to the need to keep hold of Marc Guéhi for as long as possible.

Glasner’s Frankfurt side utilised wide combinations in the half-space (white channel below) with their centre-back, centre-midfielder, wide No10, and wing-back. They enjoyed attracting a man-to-man press, isolating the far-side wing-back, before finding an outlet and playing a quick switch of play. Relatively more sides engage in a man-to-man press out wide in the Premier League than in the Bundesliga, so Palace may find real success in attracting wide pressure and switching play lots.

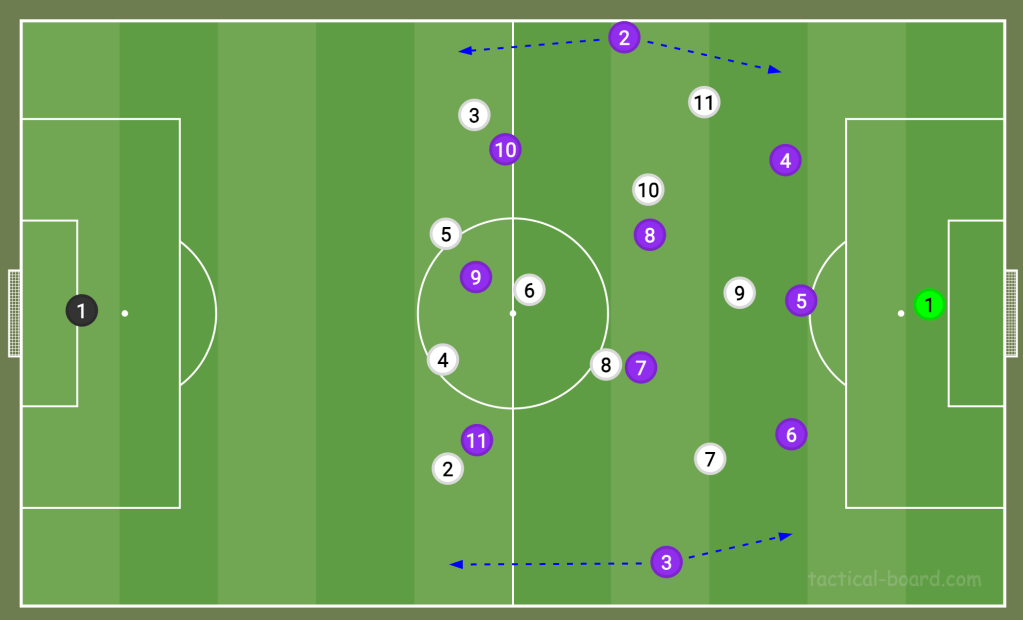

Out of possession, we will likely see a high-intensity press from Palace as soon as they lose the ball. However, sort of reminiscent of Barcelona’s old three-second rule, they will drop into an organised shape if they can’t regain possession swiftly.

He prefers a passive press, particularly from his striker, who stays remarkably close to his midfield teammates. We have often seen him deploy a pressing trap, in which the striker forces the opposition to play to the other side of the pitch, where Glasner’s wing-back has advanced and is ready to jump onto the full-back to apply pressure. (Again, this is why Palace’s centre-backs will have to be comfortable playing as momentary full-backs.)